Philosophy. Poetry. Beauty. Truth. All rays of the same light. Let them shine in your art.

Notes on Art & Filmmaking: Cinematic Beauty

Beauty in art exists only if it is experienced. It may come in the form of the beautiful, it may come in the form of the sublime, but it always translates through the relationship created between the artwork and the audience. The greater the artist is at mastering the language he or she uses to express him or herself, the greater the connection between the artwork and the audience, the greater the hope for the audience to experience the depths of art: the feelings and truths it is able to bring to the forefront from life itself.

Filmmaking Wisdom from Robert Bresson

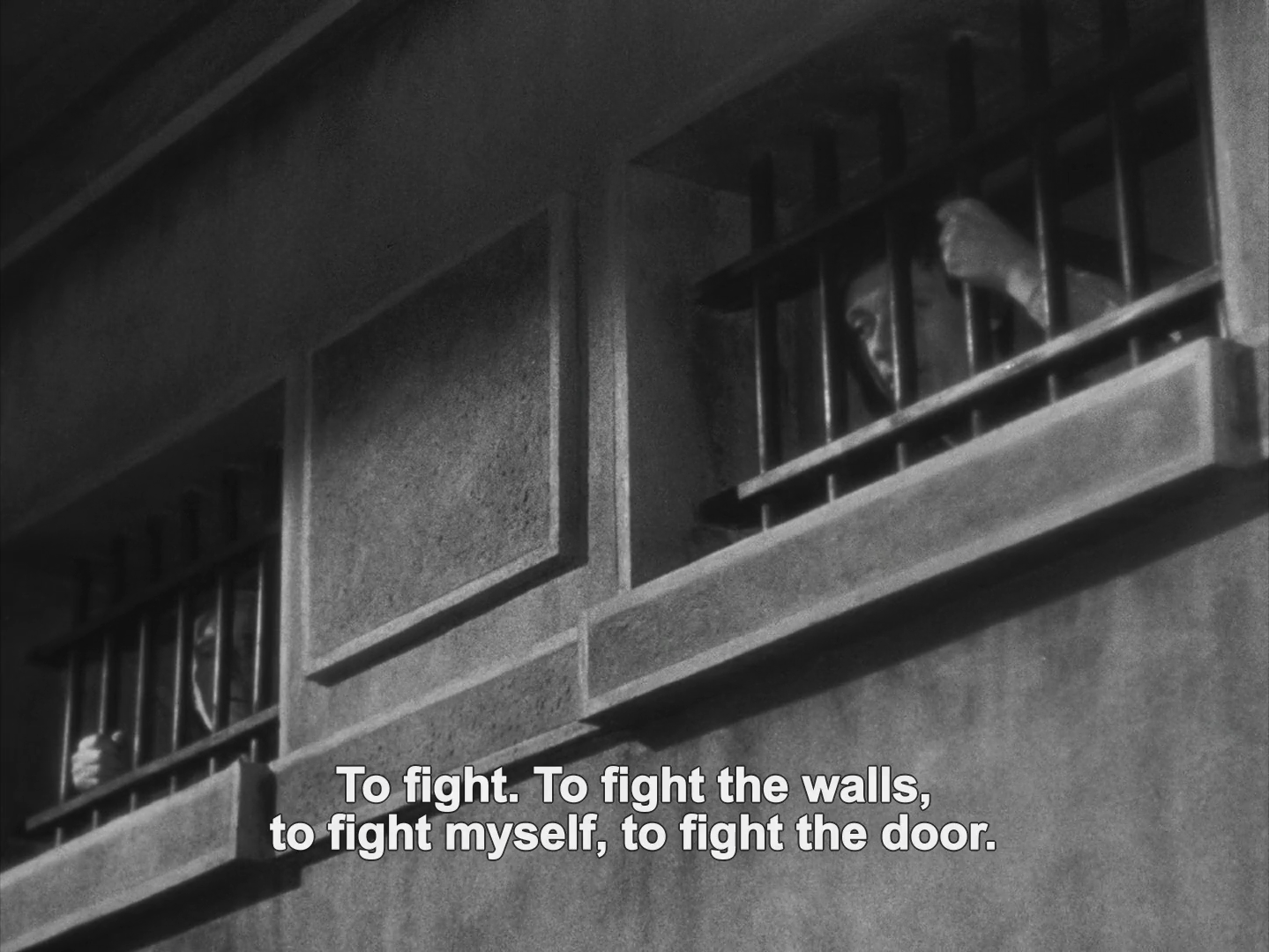

Robert Bresson's A Man Escaped: "To fight. To fight the walls, to fight myself, to fight the door."

A Man Escaped, directed by Robert Bresson, screenplay by Robert Bresson, cinematography by Léonce-Henri Burel, and edit Raymond Lamy.

When asked about the importance of Robert Bresson, Andrei Tarkovsky answered, “There are many reasons I consider Bresson a unique phenomenon in the world of film. Indeed, Bresson is one of the artists who has shown that cinema is an artistic discipline on the same level as the classic artistic disciplines such as poetry, literature, painting, and music. The second reason I admire Bresson is personal. It is the significance of his work for me—the vision of the world that it expresses. This vision of the world is expressed in an ascetic way, almost laconic, lapidary I would say. Very few artists succeed in this. Every serious artist strives for simplicity, but only a few manage to achieve it. Bresson is one of the few who has succeeded. The third reason is the inexhaustibility of Bresson’s artistic form. That is, one is compelled to consider his artistic form as life, nature itself. In that sense, I find him very close to the oriental artistic concept of Zen: depth within narrowly defined limits. Working with these forms, Bresson attempts in his films not to be symbolic; he tries to create a form as inexhaustible as nature, life itself.”

All true artists fight to convey the best path of expression within their art forms. Andrei Tarkovsky admired Robert Bresson because they shared a similar spirit when it came to filmmaking, a passion for shedding light on cinema as an art form with its own language and manner of engaging and creating profound experiences for audiences. Like Tarkovsky, Bresson epitomizes the authentic artist whose self-determination brings forth unparalleled art. He follows his vision, intuition, and own set of rules for filmmaking: he follows his own quest as an artist of cinema. His simplification or in other words purification of film elements is directed to reveal cinema not as a canvas for popular and commercial moviemaking but as a unique art form that generates unique experiences. The art and the cinematic experience together are the all-in-all. He himself expressed it as, “It’s not a question of understanding, it’s a question of feeling.” Direct yourself toward the experience to be felt by the audience, and the feeling will generate meaning.

The films of Bresson are also manifestations of the insight that you the artist are your greatest asset. One needs only to visit these Koan-like statements found in his Notes on the Cinematograph to become aware of the essence of the artist. “Metteur en scène or director. The point is not to direct someone, but to direct oneself.“ “Don't think of your film apart from the resources you have made for yourself.“ “Make visible what, without you, might never have been seen.” You are your greatest tool, your greatest resource.

Iradj Azimi on Robert Bresson: "He was a rebel, and he remained a rebel."

Iradj Azimi speaking on Robert Bresson in The Essence of Forms shares a similar sentiment to Andrei Tarkovsky: “Robert Bresson is for me an example of a real and genuine filmmaker. He obeys only certain higher, objective laws of Art…Bresson is the only person who remained himself and survived all the pressures brought by fame.”

Filmmaking Wisdom from Andrei Tarkovsky

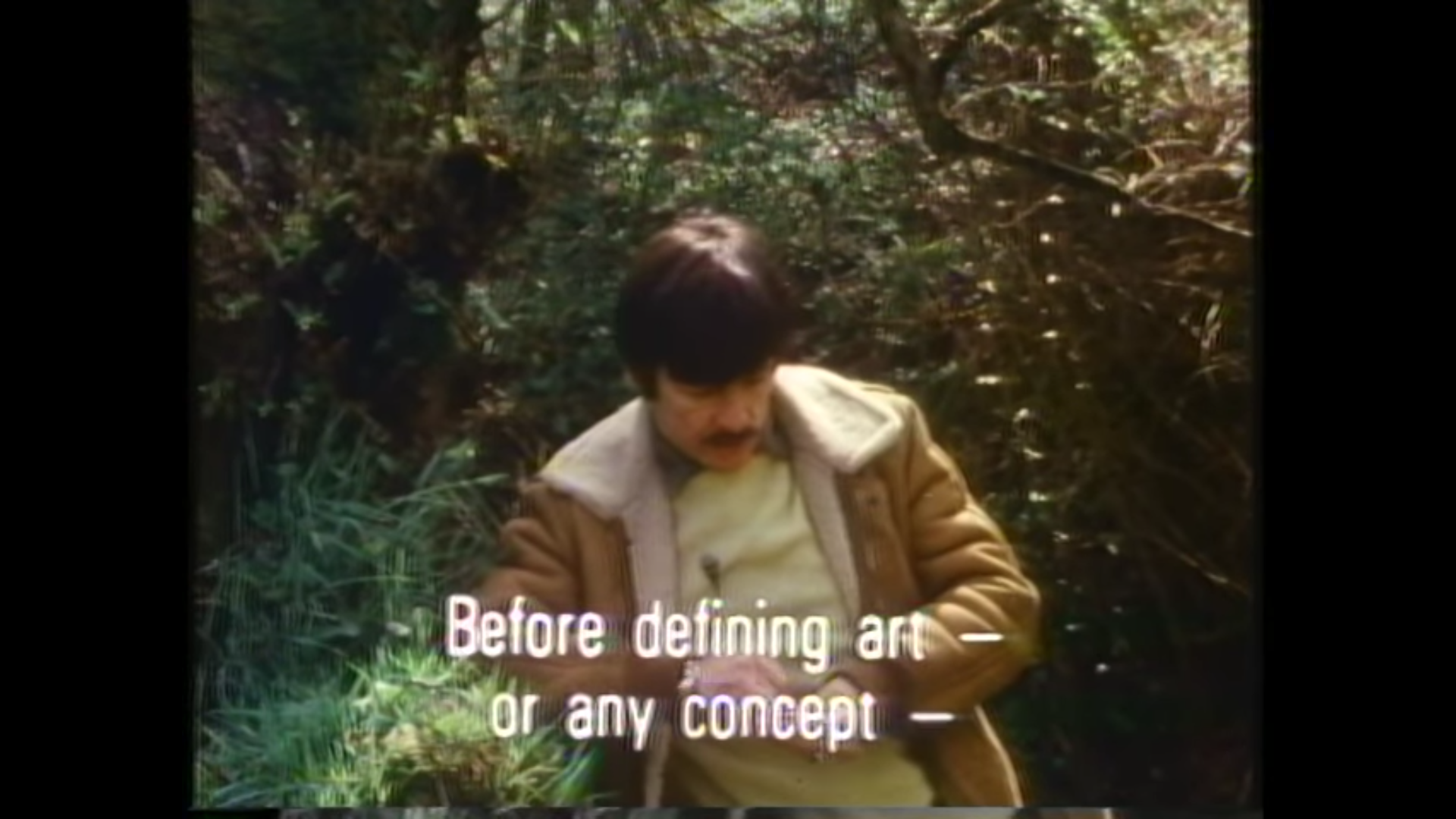

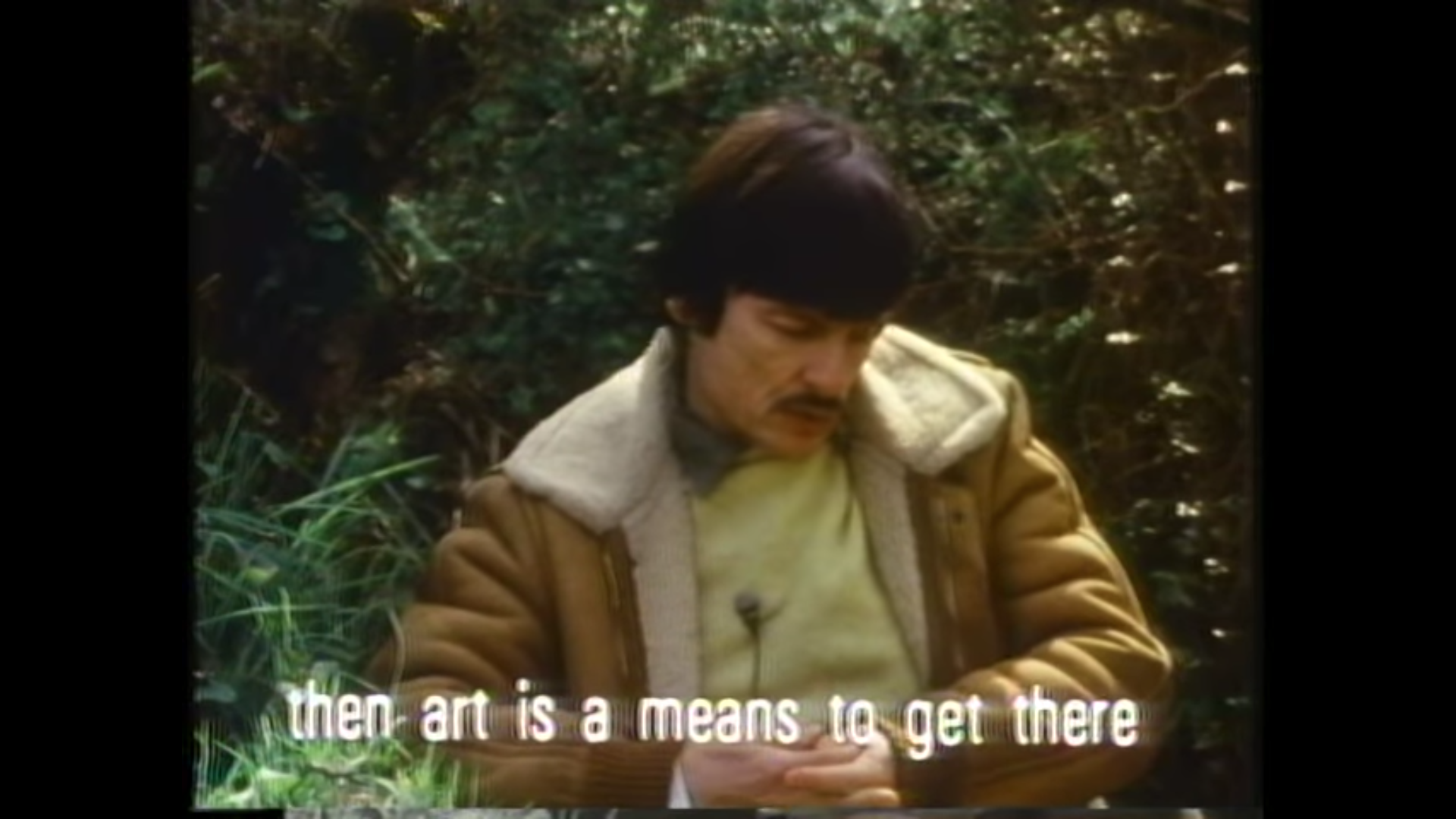

Andrei Tarkovsky in A Poet in the Cinema: "If our life tends to this spiritual enrichment, then art is a means to get there."

Andrei Tarkovsky in Donatella Baglivo's A Poet in the Cinema presents a poetic and timeless definition of art.

Andrei Tarkovsky's Mirror: "Everything will be alright."

Mirror, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrei Tarkovsky and Aleksandr Misharin, cinematography by Georgi Rerberg, music by Eduard Artemev, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova.

“Before defining art—or any concept—we must answer a far broader question: what’s the meaning of man’s life on Earth? Maybe we are here to enhance ourselves spiritually. If our life tends to this spiritual enrichment, then art is a means to get there. This, of course, in accordance with my definition of life. Art should help man in this process.” Art should help mankind in this process that Tarkovsky describes as spiritual enrichment. One of the gifts of art is its ability to present meaning to our experience of life. That is to say, art should help mankind rise toward the actualization of our best selves. As Tarkovsky writes in Sculpting in Time, “Art is a meta-language, with the help of which people try to communicate with one another; to impart information about themselves and assimilate the experience of others. Again, this has not to do with practical advantage but with realizing the idea of love, the meaning of which is in sacrifice: the very antithesis of pragmatism.”

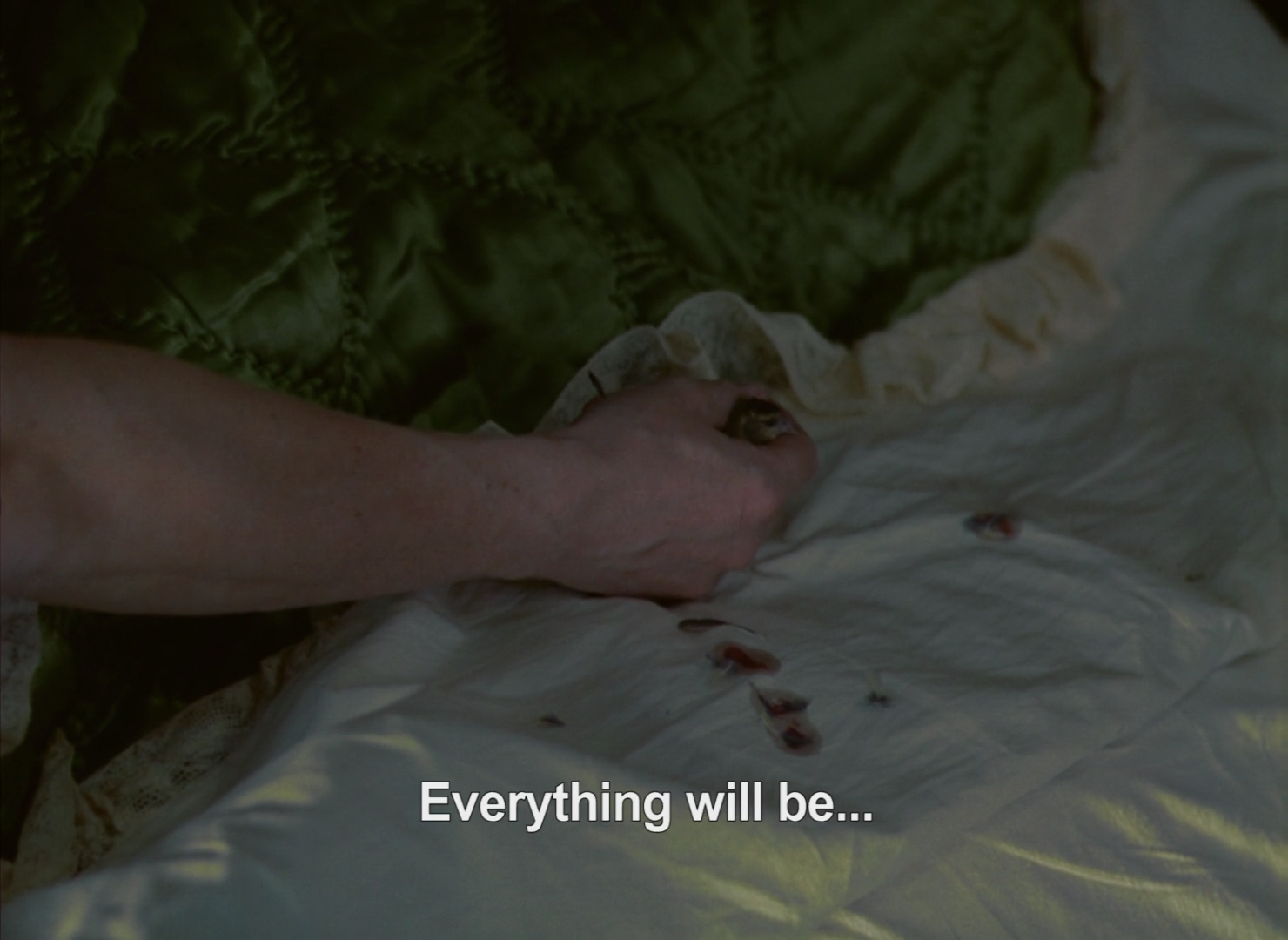

Andrei Tarkovsky in A Poet in the Cinema: "Learn to love solitude."

Andrei Tarkovsky in Donatella Baglivo's A Poet in the Cinema shares a valuable lesson and a gem of wisdom for enriching your life.

Filmmaking Wisdom from Jean-Pierre Melville

Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samouraï: "I never lose. Not really."

Le Samouraï, directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, screenplay by Jean-Pierre Melville and Georges Pellegrin, cinematography by Henri Decaë, music by François de Roubaix, and edit by Monique Bonnot and Yolande Maurette.

Highlighting the importance of Jean-Pierre Melville in film history, the book World Film Directors shares: “Long respected as an important forebear of the Nouvelle Vague, Melville has been recognized increasingly as a master in his own right, and as a director almost unique in his ability to show ‘that the cinema, for all its technical complications, can still be an extremely personal art.’” Alain Delon, the star of Melville’s masterpiece Le Samouraï, offers a similar impression on the impact of the director to the art of cinema: “He’s the greatest director I’ve had the good fortune, pleasure, and honor to work with up to this point. It’d take too long to explain. He’s wonderful. He knows more about cinema than anyone. He’s the greatest director I know, the greatest cameraman, the best at framing and lighting, the best at everything. He’s a living encyclopedia of cinema.” There is a lot of inspiration to absorb from a filmmaker like Jean-Pierre Melville.

As Melville himself put it, “You must be madly in love with cinema to create films. You also need a huge cinematic baggage.” Your awareness of film history, of the technical aspects of filmmaking, of film language, and of your cinematic style are vital to great filmmaking. Determination is another quality that emerges from that mad love for cinema. After serving in World War II, Melville applied to join the union in the French film industry and was rejected. Determined, he opened his own studio and began writing and directing his films. Later, he lost his studio to a fire, only to successfully come out of such a devastation through the need to continue making films. Obstacles always surface for the filmmaker, however, it is how one faces those obstacles that counts.

Quoting the opening line of Le Samouraï, Rui Nogueira, the author of Melville on Melville, said to Jean-Pierre Melville, “’There is no greater solitude than that of the Samurai, unless perhaps it be that of the tiger in the jungle’ might apply equally well to your situation as an independent filmmaker outside the industry.” Melville answered, “Absolutely.” A great and unique inspiration for all pursuing filmmaking, Jean-Pierre Melville shows us the importance of being true to and enriching oneself.

Creative Inspiration: All Artists Have Unique Paths

All artists have unique paths. Bresson, Tarkovsky, and Melville are three examples of artists who inspire us not only with their masterful filmmaking and timeless films but also with how they began their careers as filmmakers. It does not matter at what age you start. It does not matter from where you start. The pursuit of your dreams and passions is a never-ending quest. The right time to start is always now.

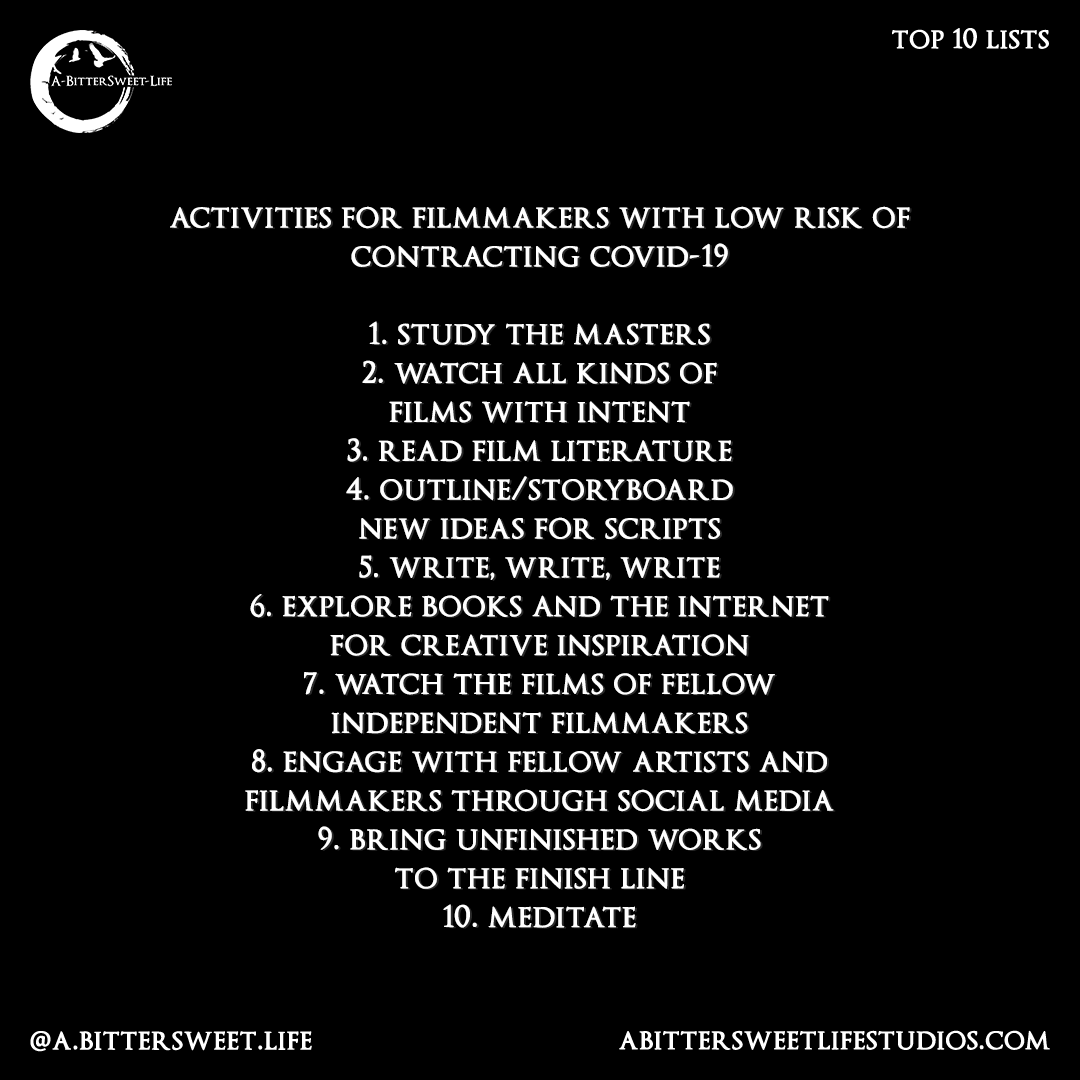

Top 10 Lists: Activities for Filmmakers with Low Risk of Contracting COVID-19

Favorite Films of Filmmakers: Andrei Tarkovsky's Top 10 Films

Filmmaking Wisdom from Andrei Tarkovsky

Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris: "But love is a feeling we can experience but never explain."

Solaris, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrei Tarkovsky and Fridrikh Gorenshteyn, cinematography by Vadim Yusov, music by Eduard Artemev, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova and Nina Marcus.

The key to great filmmaking is how you utilize your cinematic style to absorb the audience into a unique experience that can only be created through the art of cinema. Harmonizing specificity of vision and economy of meaning results in great filmmaking, that is to say your artistic voice plus finely-tuned decision-making in details through a mastery of film language equals a mindful use of your cinematic style. All great films encapsulate the filmmaker’s struggle to express him or herself within the confines of production and his or her feelings of what is and what is not meaningful to the film and the path to implementing what is in the most mindful way to the storytelling of the film.

In Sculpting in Time, Andrei Tarkovsky shares a striking thought on cinema relevant to this philosophy on great filmmaking: “I love cinema. There is still a lot that I don't know: what I am going to work on, what I shall do later, how everything will turn out, whether my work will actually correspond to the principles to which I now adhere, to the system of working hypotheses I put forward. There are too many temptations on every side: stereotypes, preconceptions, commonplaces, artistic ideas other than one's own. And really it's so easy to shoot a scene beautifully, for effect, for acclaim...But you only have to take one step in that direction and you are lost. Cinema should be a means of exploring the most complex problems of our time, as vital as those which for centuries have been the subject of literature, music and painting. It is only a question of searching, each time searching out afresh the path, the channel, to be followed by cinema. I am convinced that for any one of us our filmmaking will turn out to be a fruitless and hopeless affair if we fail to grasp precisely and unequivocally the specific character of cinema, and if we fail to find in ourselves our own key to it.”

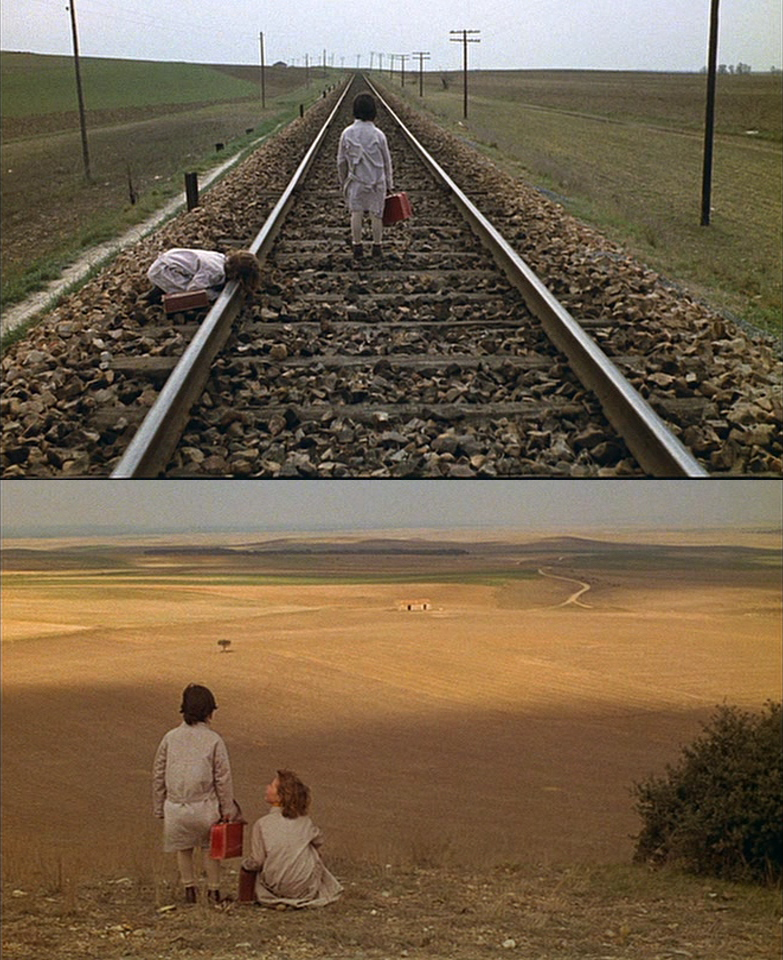

Victor Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive: "Yet if I could answer just one of these questions—what eternity is, for example—I wouldn't care if they called me mad."

The Spirit of the Beehive, directed by Victor Erice, screenplay by Victor Erice, Angel Fernández Santos, and Francisco J. Querejeta, cinematography by Luis Cuadrado, music by Luis de Pablo, and edit by Pablo G. del Amo.

“I try to achieve the beauty of truth. I always took as my motto what Robert Bresson said: ‘You don’t have to make images that are beautiful. You have to make images that are necessary.’” By invoking Robert Bresson’s philosophy on filmmaking, Victor Erice highlights the idea that the right choices in the right details is the key to creating the beauty of truth in cinema. Akira Kurosawa also alluded to this and referred to it as cinematic beauty, a beauty that is only obtainable through the efficient and effective use of film language, that when well-expressed produces a deep experience for the audience, and which is the very thing that inspires a filmmaker to create a film in the first place. For Erice, “Cinema may have no alternative other than to fall back on itself so that it may, once it has assumed its solitude, affirm itself in its dignity: a dignity conferred onto it by virtue of being the last of the artistic languages invented by man.” As an art form all to itself, cinema possesses its own unique artistic language, and it is by utilizing—making efficient and effective use of—this film language that Erice accomplishes the beauty of truth in his timeless films like The Spirit of the Beehive. Great films engage audiences with cinematic beauty through specificity of vision and economy of meaning. A great film results in cinematic beauty through the artist’s unique honing of a film to its essential poetry.

Filmmaking Wisdom from Victor Erice

Victor Erice's The Spirit of the Beehive

The Spirit of the Beehive, directed by Victor Erice, screenplay by Victor Erice, Angel Fernández Santos, and Francisco J. Querejeta, cinematography by Luis Cuadrado, music by Luis de Pablo, and edit by Pablo G. del Amo.

Wake up and see reality.

Do The Things That Express Your Soul.

Do the things that express your soul. That means putting time and energy into your work, into your dreams and passions, into your relationships with others and yourself, and that especially means utilizing time and energy with true honesty toward your life. It's about being mindful of how you live and how you desire to live. Be mindfully active in how you want to express yourself as the artist of your life.