Céline Sciamma's Portrait of a Lady on Fire

Portrait of a Lady on Fire, directed by Céline Sciamma, screenplay by Céline Sciamma, cinematography by Claire Mathon, music by Jean-Baptiste de Laubier and Arthur Simonini, and edit by Julien Lacheray.

Not everything is fleeting. Some feelings are deep.

Why the Film World Needs Bong Joon-ho

Bong Joon-ho and crew on the set of Parasite.

Oscar winner. Palme d’Or winner. Golden Globe winner. And the list goes on. Parasite, from the mastermind of cinematic storytelling Bong Joon-ho, bears a historically monumental value in the world and history of cinema. And that value goes well beyond the merits and acclaim the film has gained. As Parasite toured the world for awards, its director also carried a torch of inspiration for filmmakers to spark their own creative passions and cultivate their awareness for what it means to be an artist.

When Parasite won the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film, Bong Joon-ho started his award acceptance speech with a profoundly impactful statement about foreign cinema. “Once you overcome the 1-inch tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.” The importance of travel and getting to know different cultures is similar to the importance of experiencing art from different parts of the world. Great stories with great lessons from different points of view of life are out there for our enjoyment as well as the furthering of our awareness of our own selves and our interconnectedness to the world and life. Moreover, great films are out there as great inspirational resources for filmmakers. How would John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven, Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, and George Lucas’ Star Wars exist without the works of Akira Kurosawa? These films exist because of the cultural cross-pollination of the arts. By immersing yourself in films from beyond your national borders, you open a whole new world of great experiences.

Bong ends his Golden Globe speech with an important note for filmmakers and audiences: “We use only just one language: cinema.” Storytelling is a universally human endeavor. Of the many ways storytelling in art is able to communicate, cinema does so best by purely visual means. Cinematic storytelling is best exemplified when a film effectively utilizes the language of pure cinema—that is, a focus on the elemental characteristics of filmmaking that create an experience formed through devices that distinguish cinema from other art forms, such as the motion picture camera and its stillness and movement in compositions, the relationship between sound and image, and the rhythm of the edit. Cinematic storytelling through the means of pure cinema is what Alfred Hitchcock meant when he declared his mission as a filmmaker was to communicate through pictures, to emphasize the image over dialogue, “to give the audience something that only the movies can give you.” It’s not a big surprise why Parasite so effectively communicates with a worldwide audience. In addition to the film’s story shedding light on the worldwide issues of income inequality and the polarization of the rich and the poor, Bong Joon-ho approaches Parasite’s visual narrative with a keenly artistic awareness for the language of film. It takes a visionary filmmaker to draw upon the origins of filmmaking to exemplify the power and subtlety of the purely cinematic. Parasite’s storytelling effectiveness highlights Bong Joon-ho as this sort of visionary filmmaker.

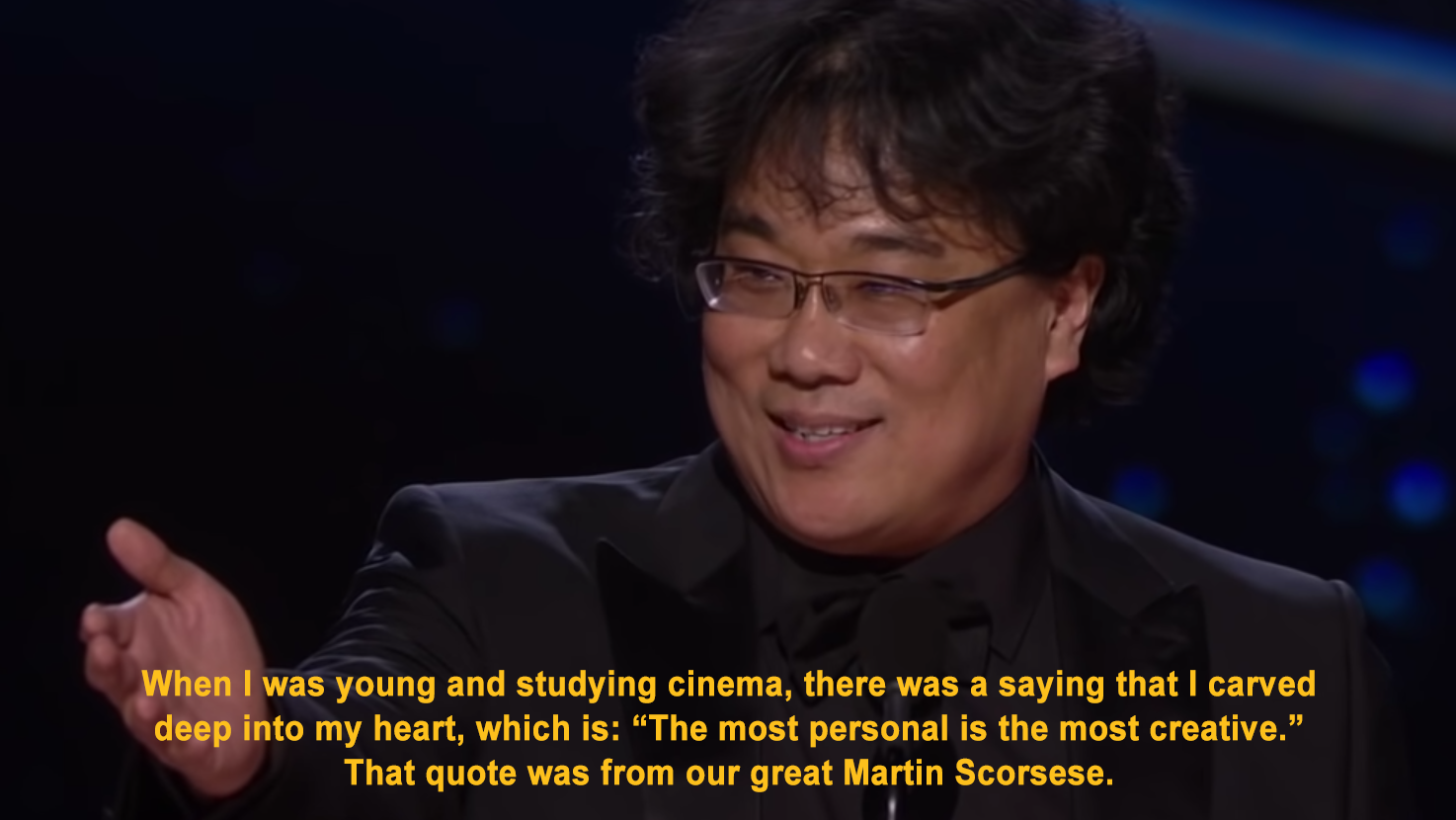

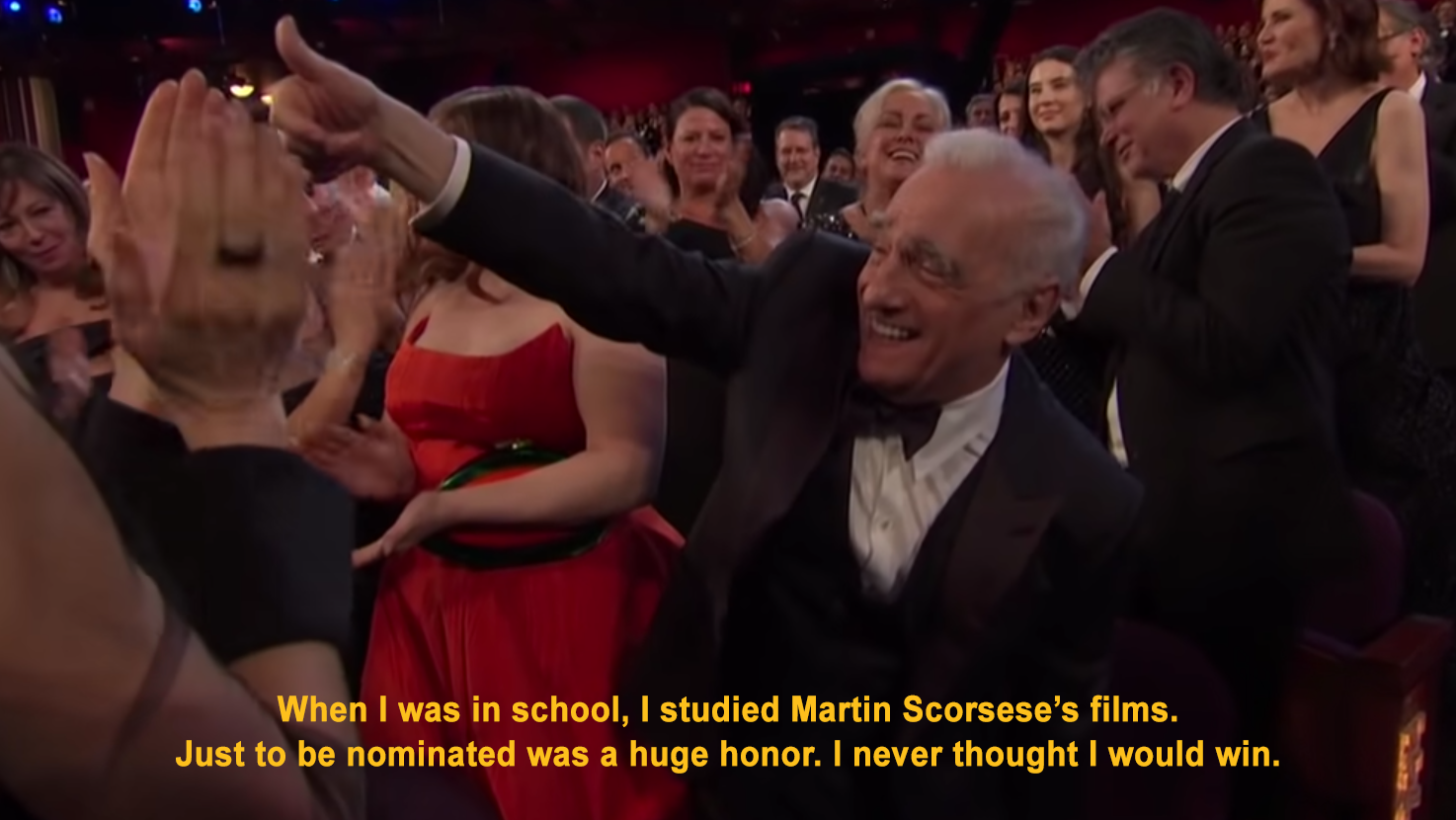

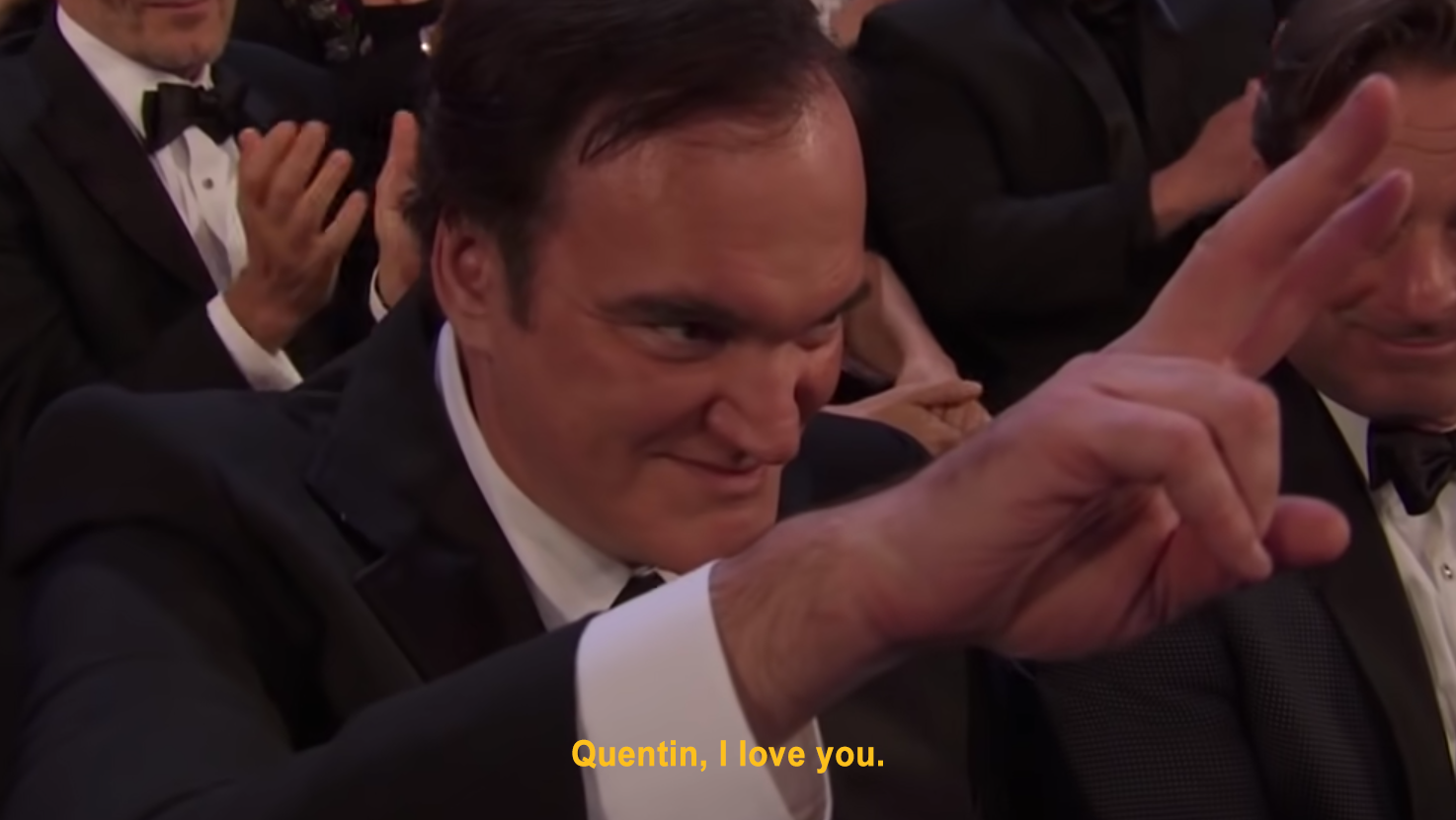

When Bong Joon-ho won the Best Director Oscar for Parasite, he again presented a memorable speech. “When I was young and studying cinema, there was a saying that I carved deep into my heart, which is: ‘The most personal is the most creative.’ That quote was from our great Martin Scorsese. When I was in school, I studied Martin Scorsese’s films. Just to be nominated was a huge honor. I never thought I would win. When people in the U.S. were not familiar with my film, Quentin always put my films on his lists. He’s here. Thank you so much. Quentin, I love you.” In addition to the admiration, love, and appreciation Bong shows his fellow filmmakers before a public audience, he offers various inspiring insights for artists and filmmakers in this speech.

“The most personal is the most creative.” While all art endeavors to reach an audience, the key to connecting with an audience is for the artist to be true to the work and to oneself. When we see a Color Field painting, we know it is by Mark Rothko without having to see the signature on the canvas. We know these imagery-filled verses are by Pablo Neruda when we read the lines “Quiero hacer contigo/ lo que la primavera hace con los cerezos. (I want to do with you/ what spring does with the cherry trees.)” There are details that mark the nature and presence of the artist in his or her work. The most personal is the most creative and, as a result, the most unique. For all artists: be true to your style, be true to you.

Bong also hints at one of the most valuable ways of enriching your artistic style when he honors Martin Scorsese in this speech. In mentioning his studies of Martin Scorsese’s films, Bong brings to mind Scorsese’s memorable advice to young filmmakers: “I’m often asked by younger filmmakers, ‘Why do I need to look at old movies?’ I’ve made a number of pictures in the past twenty years. And the response I find that I have to give them is that I still consider myself a student. The more pictures I’ve made in the past twenty years the more I realize I really don’t know. And I’m always looking for something to, something or someone that I could learn from. I tell them, I tell the younger filmmakers and the young students that I do it like painters used to do, or painters do: study the old masters, enrich your palette, expand your canvas. There’s always so much more to learn.” In studying the old masters, you nourish your evolution as an artist and further your understanding of who you are as an artist. You also discover that the details, ideas, and habits that resonate from others and their works are often reflections of your own artistic voice.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” said Isaac Newton. “The dwarf sees farther than the giant, when he has the giant’s shoulder to mount on,” wrote Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Study the old masters in order to enrich your palette and in order to go further than you could all by yourself. As Jim Jarmusch shares in his Golden Rules to Filmmaking: “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: ‘It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to.’”

After Bong Joon-ho salutes Martin Scorsese, he mentions the support he has received from fellow filmmaker Quentin Tarantino and shows appreciation and gratitude for his endorsement. Here Bong highlights the importance of community, of building your tribe and supporting your fellow artists. Together, we grow stronger. Together, we blossom because we nourish one another. A tribe of artists cultivates creative energy for the use of all. In a world where everyone is fighting to make their mark, the true fight is won by helping each other to make their mark. Thus, it is invaluable to find your tribe, the people who nourish you in your career and work.

Bong Joon-ho has presented the world a 21st Century masterpiece of cinema with Parasite, which enters a filmography of unique, thrilling, and deeply layered films. He proves that a film can be both entertainment and art, or rather that a film that is made out of meaningful and genuine artistic expression can engage audiences around the world. It was magnificent to witness Parasite win award after award, especially in a system that often disengages with the perspective of those who love the art of cinema. Truly, the film world needs Bong Joon-ho.

Filmmaking Wisdom from Martin Scorsese

Martin Scorsese's Taxi Driver: "A sense of some place to go."

Taxi Driver, directed by Martin Scorsese, screenplay by Paul Schrader, cinematography by Michael Chapman, music by Bernard Herrmann, and edit by Tom Rolf and Melvin Shapiro.

“I think it is good if a young person wants to express themselves and take a video camera and go out. They’re going to find that they have to frame the image, and in framing the image, they’re going to find that they have to interpret what they want to say to an audience. And how do you point the audience’s eye to look where you want them to look and to get the point, the emotional, psychological point that you want to get across to them. They’re going to have to make that decision. The real making of the filmmaker is when they look through that viewfinder to tell the story, and I don’t mean just telling a story, you know, boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy gets girl. No, I mean a story could be rain hitting a tree, leaves. That could be your story, you know, but how?” Martin Scorsese’s “how” conveys the understanding that the art of cinema has its own language and vocabulary, and it is through the mastery of its grammar that a filmmaker truly creates a work of art.

The foundation of a great film is not so much what story you are telling but how you tell your story, how you express your film, how through your decision in details you engage and impact your audience with ideas, action, and emotions to authentically communicate your cinematic vision. Scorsese says it perfectly when he states, “As King Vidor said, ‘The cinema is the greatest means of expression ever invented, but it is an illusion more powerful than any other, and should therefore be in the hands of the magicians and the wizards who could bring it to life.’”

Filmmaking Wisdom from Bong Joon-ho

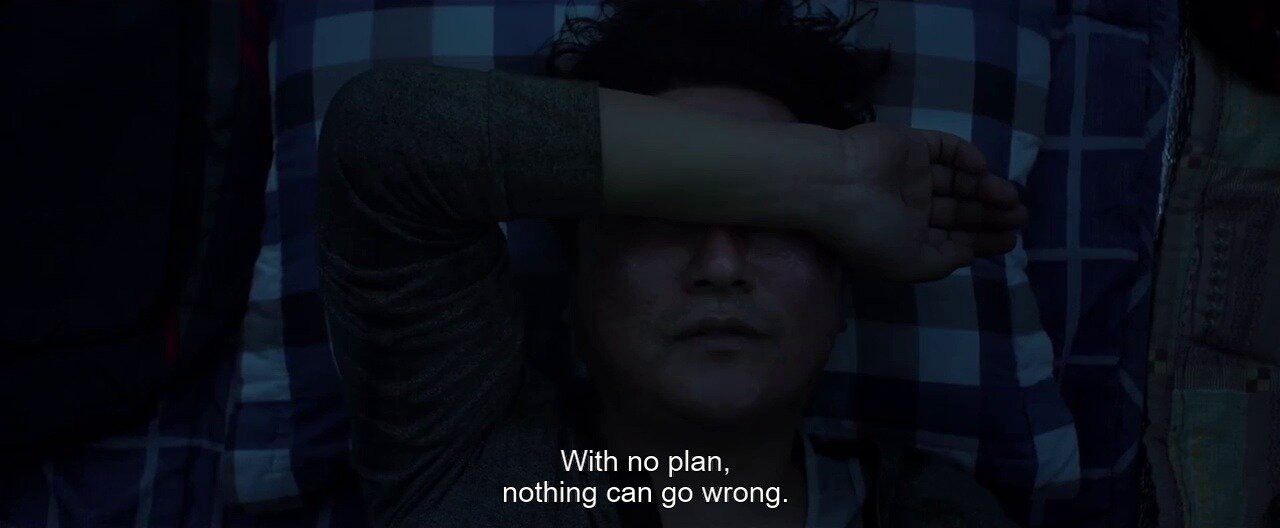

Bong Joon-ho's Parasite: "With no plan, nothing can go wrong."

Parasite, directed by Bong Joon-ho, screenplay by Bong Joon-ho and Han Jin-won, cinematography by Hong Kyung-pyo, music by Jeong Jae-il, and edit by Yang Jin-mo.

Speaking on Parasite, Bong Joon-ho shares a fundamental insight on the ability of art to communicate to world audiences: “When directing the movie, I tried to express a sentiment specific to the Korean culture, and I thought that…it was full of Koreanness if seen from an outsider’s perspective, but upon screening the film after completion, all the responses from different audiences were pretty much the same, which made me realize that the topic was universal, in fact. Essentially, we all live in the same country…called Capitalism, which may explain the universality of their responses.” Timeless art confirms a valuable quality in artistic expression: what is most personal is most universal. The deeper the artist is in his or her specificity of vision, the more deeply rooted he or she is in the universal. Personal experiences resonate in universal feelings. Therefore, as a filmmaker, always be true to you, and what stems from that will be experienced as authentic by your audience.

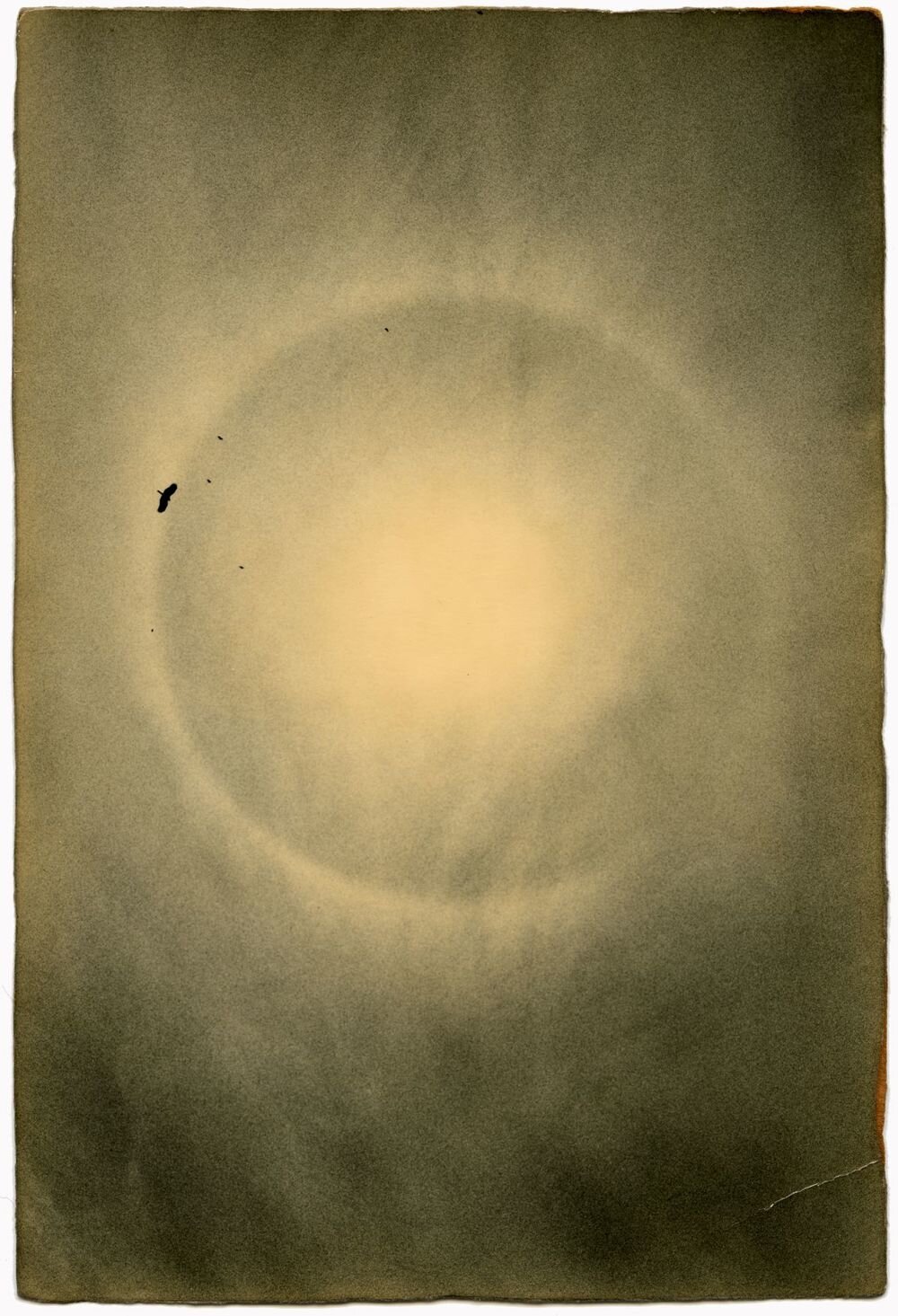

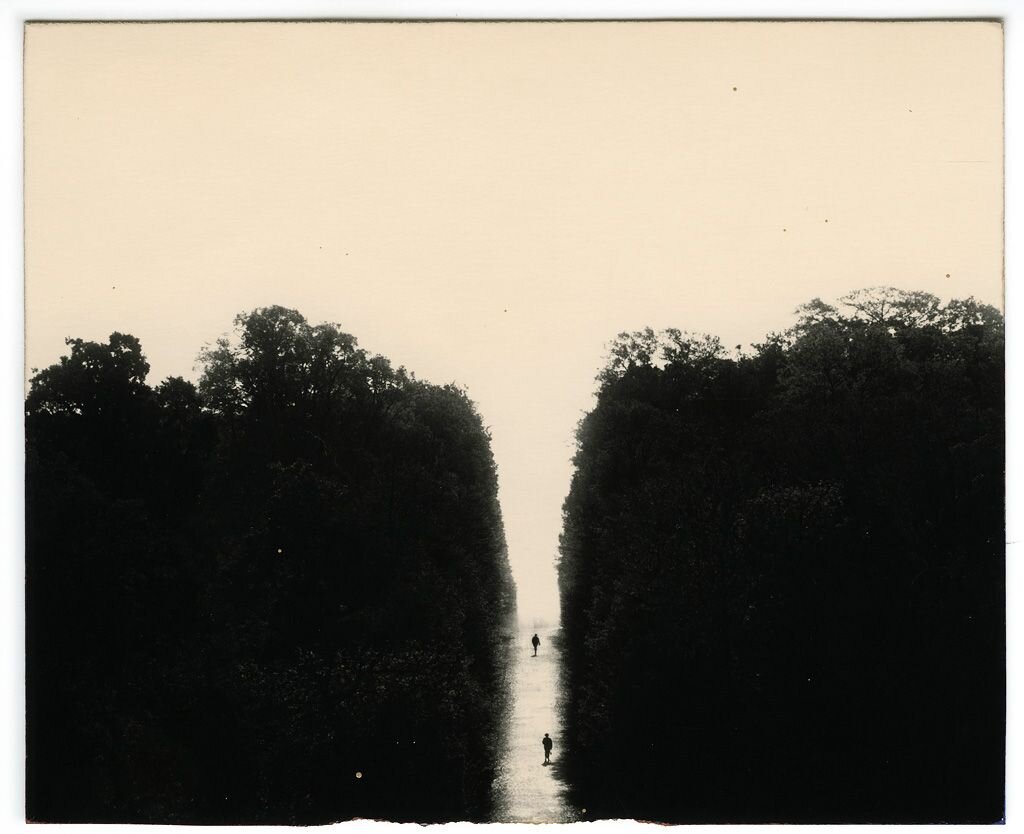

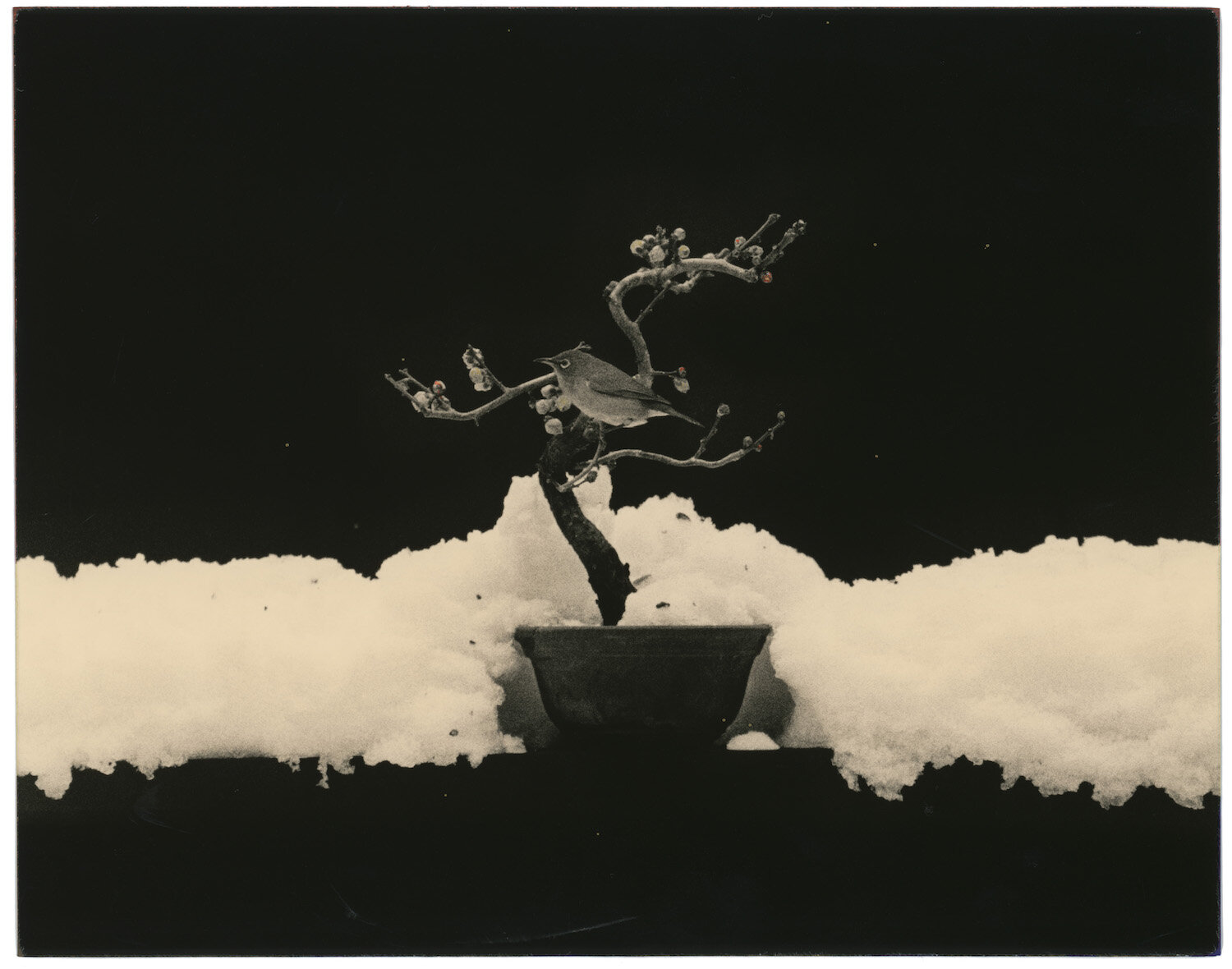

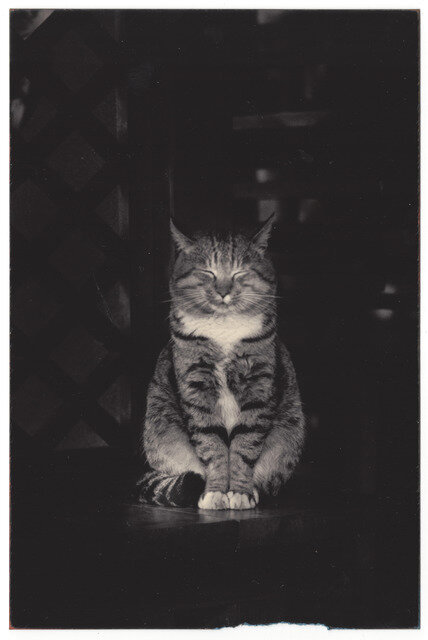

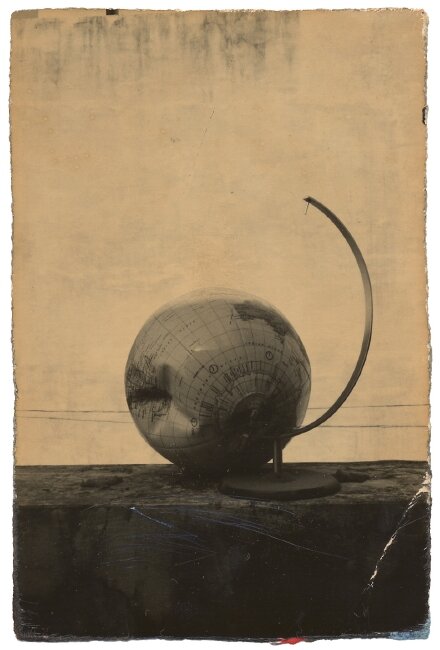

The Photography of Masao Yamamoto

”In Tao Te Ching , an ancient Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu wrote, ‘A great presence is hard to see. A great sound is hard to hear. A great figure has no form.’ What he means is that the world is full of noises that we humans are not capable of hearing. For example, we cannot hear the noises created by the movement of the universe. Although these sounds exist, we ignore them altogether and act as if only what we can hear exists. Lao Tzu teaches us to humbly accept that we only play a small part in the grand scheme of the universe.” If Zen philosophy and haiku poetry could take shape in visual form, then it would be realized in the photography of Masao Yamamoto. Through his pursuit of beauty and the belief that beauty is an essential aspect in the enrichment of mankind, Yamamoto reveals the extraordinary in the ordinary, the infinite in the finite, timelessness in impermanence. His photographs are meditative artworks that bring the viewer closer to the essence of things, toward the experience of becoming aware of one's precious witnessing of life.

Masao Yamamoto: “Long ago, there was a man named Ryokan, who was a calligrapher and a poet. I have an enormous amount of respect for him. In one of his haikus he describes simply the movement of a leaf trembling as it falls. But in reality, this poem can be interpreted in several ways. For example, the falling leaf could be a metaphor for life, the right side up, the bad, and the reverse side, the good. From this simple natural phenomenon he speaks of much deeper things. I find this remarkable. I would like to take these kinds of photos. For me a good photo is one that soothes. Makes us feel kind, gentle. A photo that gives us courage, that reminds us of good memories, that makes people happy.”

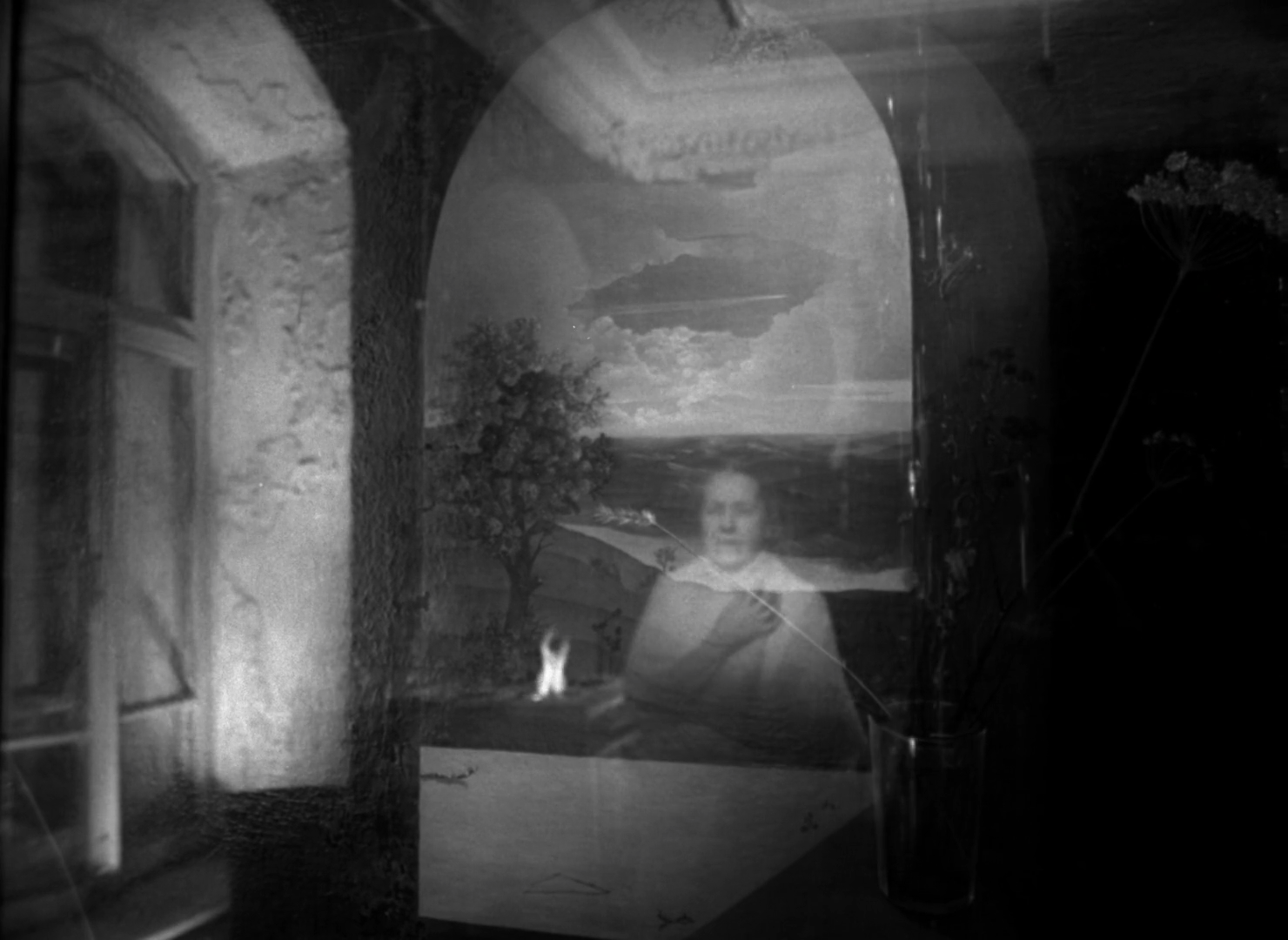

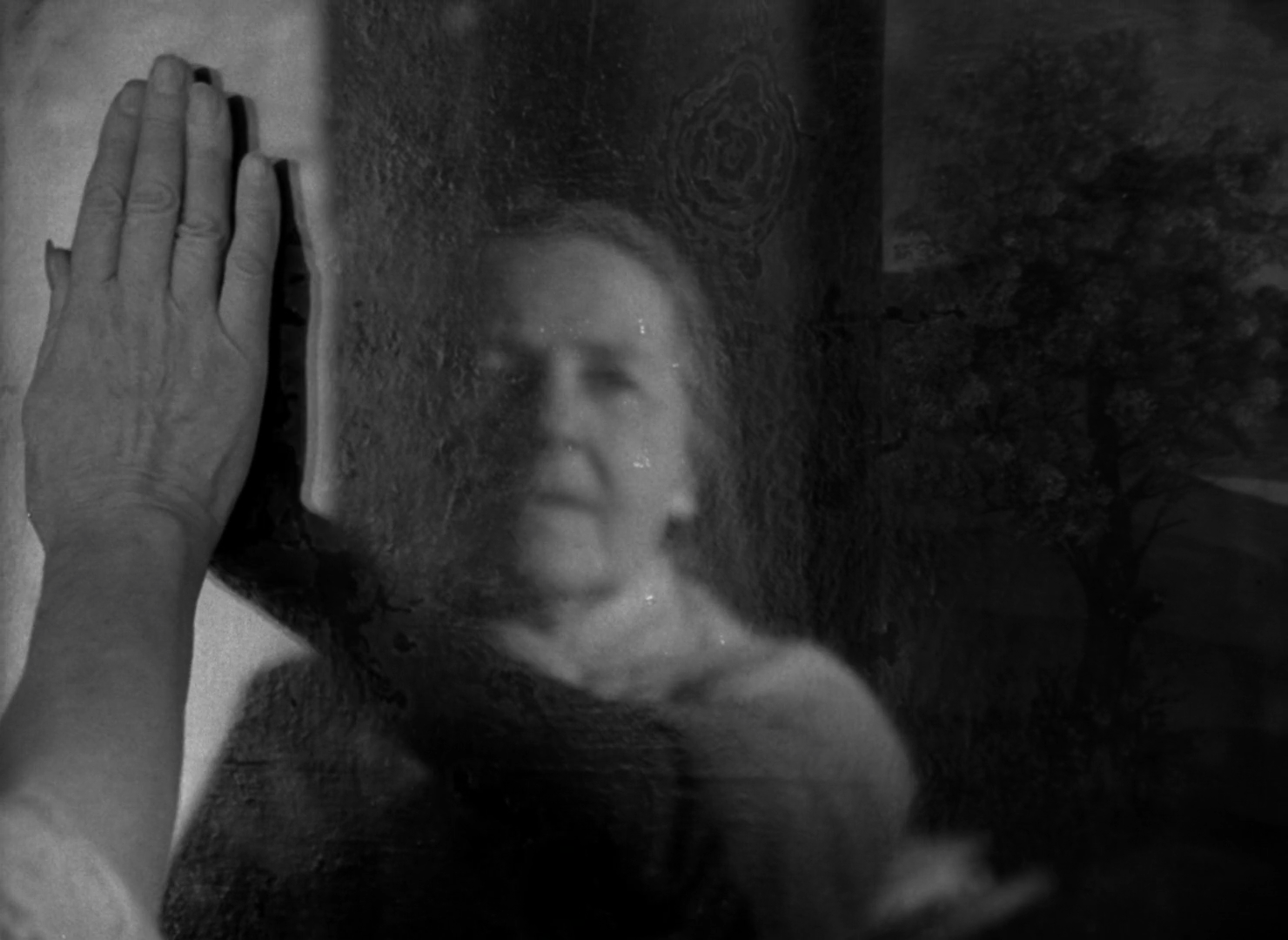

Film Technique: The Mirror Shot in Andrei Tarkovsky's Mirror

Mirror, directed by Andrei Tarkovsky, screenplay by Andrei Tarkovsky and Aleksandr Misharin, cinematography by Georgi Rerberg, music by Eduard Artemev, and edit by Lyudmila Feyginova.

"Mirrors are the essence of movies." When we reflect on Andrei Tarkovsky's poetic direction of film language, we can not help but think Tarkovsky would agree with Nicolas Roeg's statement on the use of mirrors in filmmaking. The mirror shot carries the essence of the frame within a frame technique and the feel of the mise-en-abyme, as in the metaphysical meaning manifested by the story within a story technique found in literature and that translates into the visual arts to great effect. Call to mind Gabriel Garcia Marquez's One Hundred Years of Solitude in literature. In painting, think of Las Meninas by Diego Velázquez. In cinema, consider Orson Welles' Citizen Kane and The Lady from Shanghai. The mirror is an impactful tool for artistic expression. In the hands of a filmmaker who emphasizes the effective use of film language, the mirror furthers visual, emotional, and psychological depth, and in the hands of a filmmaker like Andrei Tarkovsky, it furthers poetic depth, as seen in his masterpiece Mirror. The mirror shot is a shot of intimacy that allows a narrative to connect with an audience in terms of contemplation, discovery, desire, identity, memory, persona and truth, and much more.

Filmmaking Wisdom from Andrei Tarkovsky

There Is A Fine Line Between What May Be Brilliant And What Is Brilliant.

*Action.* 🎬 Go for brilliant. Your passions, your dreams, and your visions are ideas to bring to life, and the key to materializing these ideas is action, is execution. There is a fine line between what may be brilliant and what is brilliant. To bring the brilliant to life you must move toward it and embrace it.

Maya Angelou: "This Is Your Life. This Is Your World."

The powerhouse of inspiration Maya Angelou said it perfectly: "There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story inside you." She also shared, "All great achievements require time." Great things take time. However, they require action to reach their fulfillment. As she expresses here, "Live your life in a way that you will not regret years of useless virtue and inertia and timidity. Take up the battle." This is your life. Make what is yours count.

Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai: "By Protecting Others, You Save Yourself."

Seven Samurai, directed by Akira Kurosawa, screenplay by Akira Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto, and Hideo Oguni, cinematography by Asakazu Nakai, music by Fumio Hayasaka, and edit by Akira Kurosawa.

A constant and engaging quality of Akira Kurosawa's films is their presentation of a humanist gaze in a cinematic narrative. For Kurosawa, "The backbone of a good film is the filmmaker’s humane character. If we are not honest to ourselves, we will never be able to make decent films…A person, who is able to make good films, knows how to find his or her way into the viewer’s heart." Emphasizing the individual and collective value and agency of human beings and a concern for humankind's relation to the world, Kurosawa champions characters who show love toward humanity and who use their faculties and abilities to advance human welfare. As he shares, "The characters in my films try to live honestly and make the most of their lot in life. I believe you must live honestly and develop your abilities to the fullest. People who do this are the real heroes." This philosophy is felt in the memorable words of the wise and honorable Kambei Shimada from Seven Samurai, "By protecting others, you save yourself. If you only think of yourself, you'll only destroy yourself."

Filmmaking Wisdom from Akira Kurosawa

Akira Kurosawa: Advice for Creatives

Akira Kurosawa and crew on the set of Seven Samurai.

What is the trick to success? How does one nourish his or her creativity? With over 30 director credits in a career spanning 57 years, Akira Kurosawa stands as a legend among legends whose work shines as a monument of artistic and personal achievement. In this video, the celebrated filmmaker of masterpieces, like Seven Samurai and Rashomon, offers impactful insight on achieving one's goals and on the creative process, making his advice for creatives an essential lesson for artists and filmmakers.

Jim Jarmusch's The Limits of Control: "From a Dream or a Film."

The Limits of Control, directed by Jim Jarmusch, screenplay by Jim Jarmusch, cinematography by Christopher Doyle, music by Boris, and edit by Jay Rabinowitz.

In one of his golden rules to filmmaking, Jim Jarmusch shares, “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: ‘It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to.’”

This scene from The Limits of Control perfectly exemplifies Jarmusch’s insight on authenticity versus originality in art. Rather than copying a scene from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, he obliquely touches upon it through the poetic use of dialogue. Many greats artists have shared similar views to Jarmusch’s golden rule of taking the inspiring and transforming it to something uniquely yours. Poet T.S. Eliot wrote, “Immature poets imitate; mature poets steal; bad poets deface what they take, and good poets make it into something better, or at least something different. The good poet welds his theft into a whole of feeling which is unique, utterly different from that from which it was torn; the bad poet throws it into something which has no cohesion. A good poet will usually borrow from authors remote in time, or alien in language, or diverse in interest.” Over time, we find artists echoing Eliot’s words, from Igor Stravinsky’s “Lesser artists borrow; great artists steal,” to Pablo Picasso’s “Good artists copy; great artists steal,” to Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Rules to Filmmaking. Nevertheless, the essence of the message remains the same. What resonates with inspiration, absorb it. What fuels your imagination, take in. Nourish your creativity, and cultivate your unique artistic voice.

Jim Jarmusch's Golden Rules to Filmmaking

“Jim Jarmusch” by Patrick Swirc.

A monumental figure of the independent filmmaking world, Jim Jarmusch offers 5 invaluable golden rules to filmmaking that will inspire and fuel filmmakers of all experience levels. At the heart of these rules is an understanding for mindfulness and self-awareness in the making of films, and though Jarmusch offers his insights in the form of rules, it is important to note the director’s very first words: There are no rules. This key declaration expresses the simple truth that each filmmaker has his or her own personal journey to take through the world of cinema. Get inspired by Jim Jarmusch and his golden rules to filmmaking.

Rule #1

There are no rules. There are as many ways to make a film as there are potential filmmakers. It’s an open form. Anyway, I would personally never presume to tell anyone else what to do or how to do anything. To me that’s like telling someone else what their religious beliefs should be. Fuck that. That’s against my personal philosophy—more of a code than a set of “rules.” Therefore, disregard the “rules” you are presently reading, and instead consider them to be merely notes to myself. One should make one’s own “notes” because there is no one way to do anything. If anyone tells you there is only one way, their way, get as far away from them as possible, both physically and philosophically.

Rule #2

Don’t let the fuckers get ya. They can either help you, or not help you, but they can’t stop you. People who finance films, distribute films, promote films and exhibit films are not filmmakers. They are not interested in letting filmmakers define and dictate the way they do their business, so filmmakers should have no interest in allowing them to dictate the way a film is made. Carry a gun if necessary.

Also, avoid sycophants at all costs. There are always people around who only want to be involved in filmmaking to get rich, get famous, or get laid. Generally, they know as much about filmmaking as George W. Bush knows about hand-to-hand combat.

Rule #3

The production is there to serve the film. The film is not there to serve the production. Unfortunately, in the world of filmmaking this is almost universally backwards. The film is not being made to serve the budget, the schedule, or the resumes of those involved. Filmmakers who don’t understand this should be hung from their ankles and asked why the sky appears to be upside down.

Rule #4

Filmmaking is a collaborative process. You get the chance to work with others whose minds and ideas may be stronger than your own. Make sure they remain focused on their own function and not someone else’s job, or you’ll have a big mess. But treat all collaborators as equals and with respect. A production assistant who is holding back traffic so the crew can get a shot is no less important than the actors in the scene, the director of photography, the production designer or the director. Hierarchy is for those whose egos are inflated or out of control, or for people in the military. Those with whom you choose to collaborate, if you make good choices, can elevate the quality and content of your film to a much higher plane than any one mind could imagine on its own. If you don’t want to work with other people, go paint a painting or write a book. (And if you want to be a fucking dictator, I guess these days you just have to go into politics…).

Rule #5

Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: “It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to.”

Filmmaking Wisdom from David Lynch

Film Technique: Chiaroscuro in David Lynch's Mulholland Drive

Mulholland Drive, directed by David Lynch, screenplay by David Lynch, cinematography by Peter Deming, music by Angelo Badalamenti, and edit by Mary Sweeney.

Chiaroscuro translates to "light-dark" (chiaro: light or clear; oscuro: dark or obscure). In visual art, the term means the use of deep variations in and subtle gradations of light and shadow to create three-dimensional volume on a flat surface. The painter Caravaggio is well-known for his effective use of chiaroscuro through his blending of high contrast and a single focused light source. Where the light focuses your attention on his subjects and storytelling, the deep contrast intensifies the drama of his scenes. Other painters who used chiaroscuro are Leonardo da Vinci, Artemisia Gentileschi, Rembrandt, Johannes Vermeer, and Francisco Goya.

In film, the chiaroscuro technique can enrich a film's visual narrative and emotional depth. When we consider German Expressionism and Film Noir—for example, F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu and Orson Welles' Touch of Evil, respectively—we see how the technique creates specific moods and engages us into the atmosphere and drama of a scene. Time-travel to Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather and David Lynch's Mulholland Drive, we realize the chiaroscuro technique is a timeless tool for filmmakers and cinematic storytelling. David Lynch especially utilizes the technique to great effect. By emphasizing the interplay of light and shadow, Lynch interjects a sense of mystery into his films while at the same time heightening our sense of reality in his visual narratives.

Patti Smith: "Build a Good Name."

Value your purpose through conscious action and pursuit of what you love. Be uncompromisingly relentless, especially when you see what others can not. What matters is to know what you want and to pursue it. What nourishes that is building a good name. Your name is its own currency. Cherish these words from Patti Smith, and cherish the value that comes from building a good name.