Bong Joon-ho and crew on the set of Parasite.

Oscar winner. Palme d’Or winner. Golden Globe winner. And the list goes on. Parasite, from the mastermind of cinematic storytelling Bong Joon-ho, bears a historically monumental value in the world and history of cinema. And that value goes well beyond the merits and acclaim the film has gained. As Parasite toured the world for awards, its director also carried a torch of inspiration for filmmakers to spark their own creative passions and cultivate their awareness for what it means to be an artist.

When Parasite won the Golden Globe for Best Foreign Film, Bong Joon-ho started his award acceptance speech with a profoundly impactful statement about foreign cinema. “Once you overcome the 1-inch tall barrier of subtitles, you will be introduced to so many more amazing films.” The importance of travel and getting to know different cultures is similar to the importance of experiencing art from different parts of the world. Great stories with great lessons from different points of view of life are out there for our enjoyment as well as the furthering of our awareness of our own selves and our interconnectedness to the world and life. Moreover, great films are out there as great inspirational resources for filmmakers. How would John Sturges’ The Magnificent Seven, Sergio Leone’s A Fistful of Dollars, and George Lucas’ Star Wars exist without the works of Akira Kurosawa? These films exist because of the cultural cross-pollination of the arts. By immersing yourself in films from beyond your national borders, you open a whole new world of great experiences.

Bong ends his Golden Globe speech with an important note for filmmakers and audiences: “We use only just one language: cinema.” Storytelling is a universally human endeavor. Of the many ways storytelling in art is able to communicate, cinema does so best by purely visual means. Cinematic storytelling is best exemplified when a film effectively utilizes the language of pure cinema—that is, a focus on the elemental characteristics of filmmaking that create an experience formed through devices that distinguish cinema from other art forms, such as the motion picture camera and its stillness and movement in compositions, the relationship between sound and image, and the rhythm of the edit. Cinematic storytelling through the means of pure cinema is what Alfred Hitchcock meant when he declared his mission as a filmmaker was to communicate through pictures, to emphasize the image over dialogue, “to give the audience something that only the movies can give you.” It’s not a big surprise why Parasite so effectively communicates with a worldwide audience. In addition to the film’s story shedding light on the worldwide issues of income inequality and the polarization of the rich and the poor, Bong Joon-ho approaches Parasite’s visual narrative with a keenly artistic awareness for the language of film. It takes a visionary filmmaker to draw upon the origins of filmmaking to exemplify the power and subtlety of the purely cinematic. Parasite’s storytelling effectiveness highlights Bong Joon-ho as this sort of visionary filmmaker.

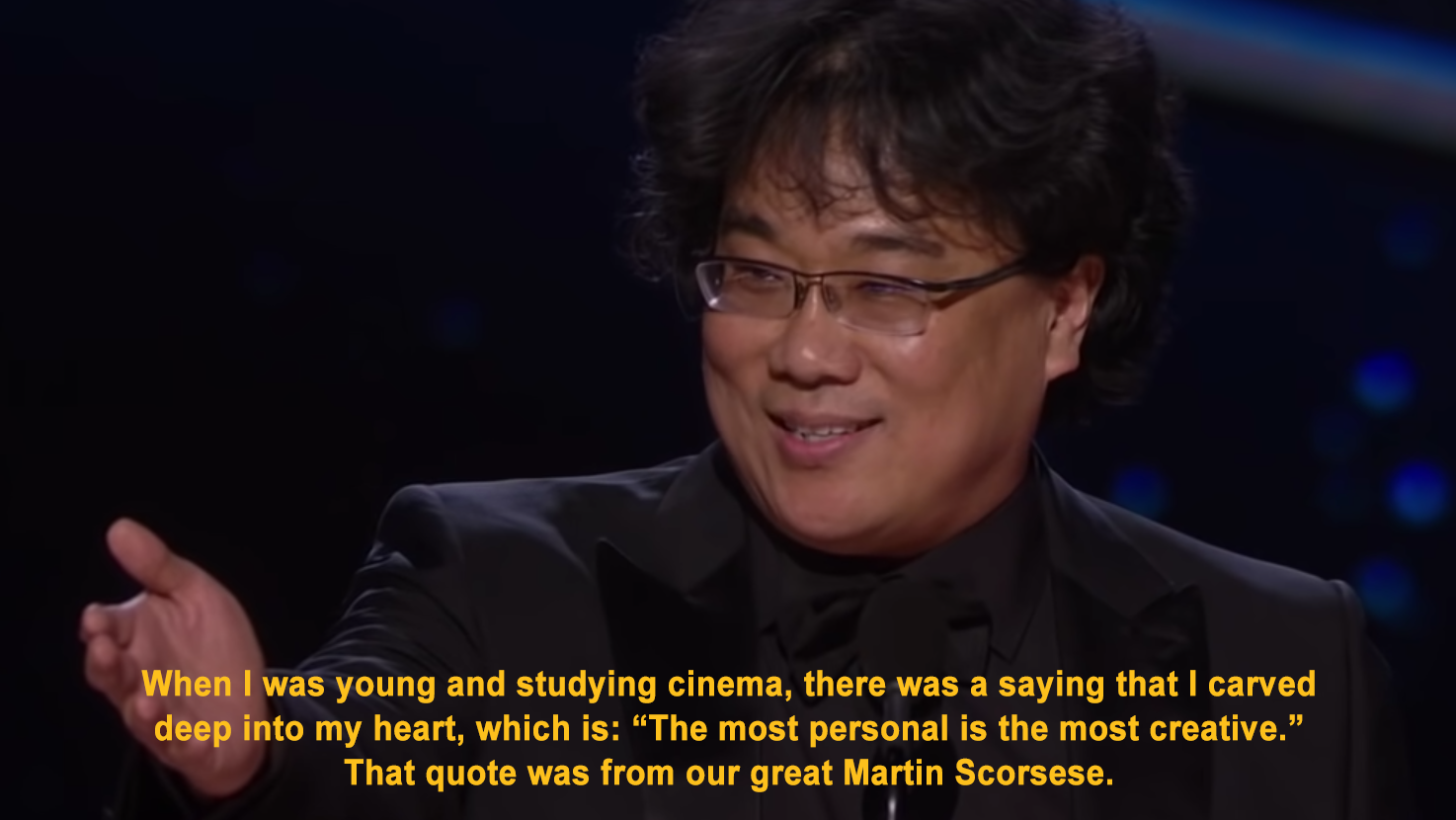

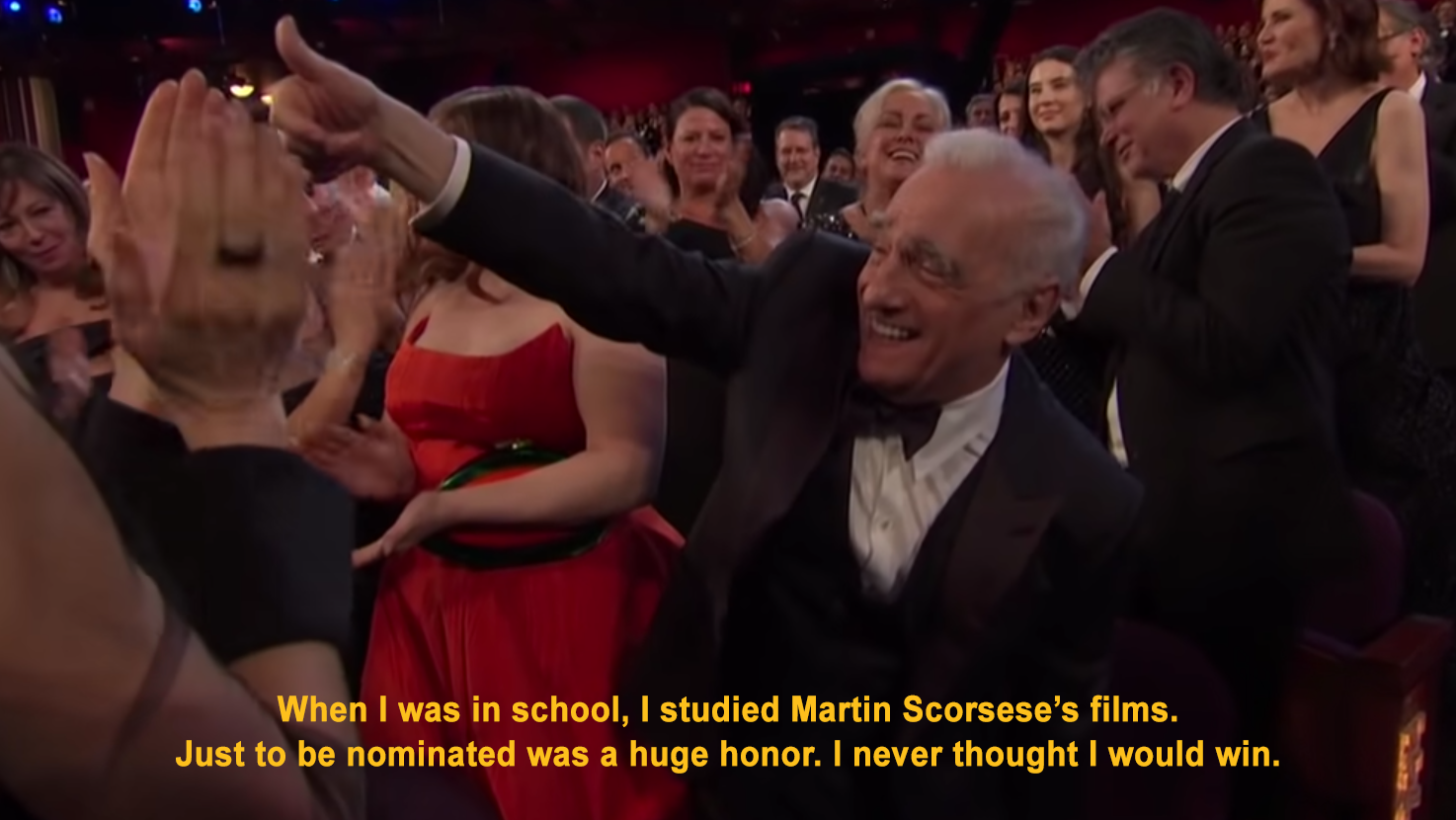

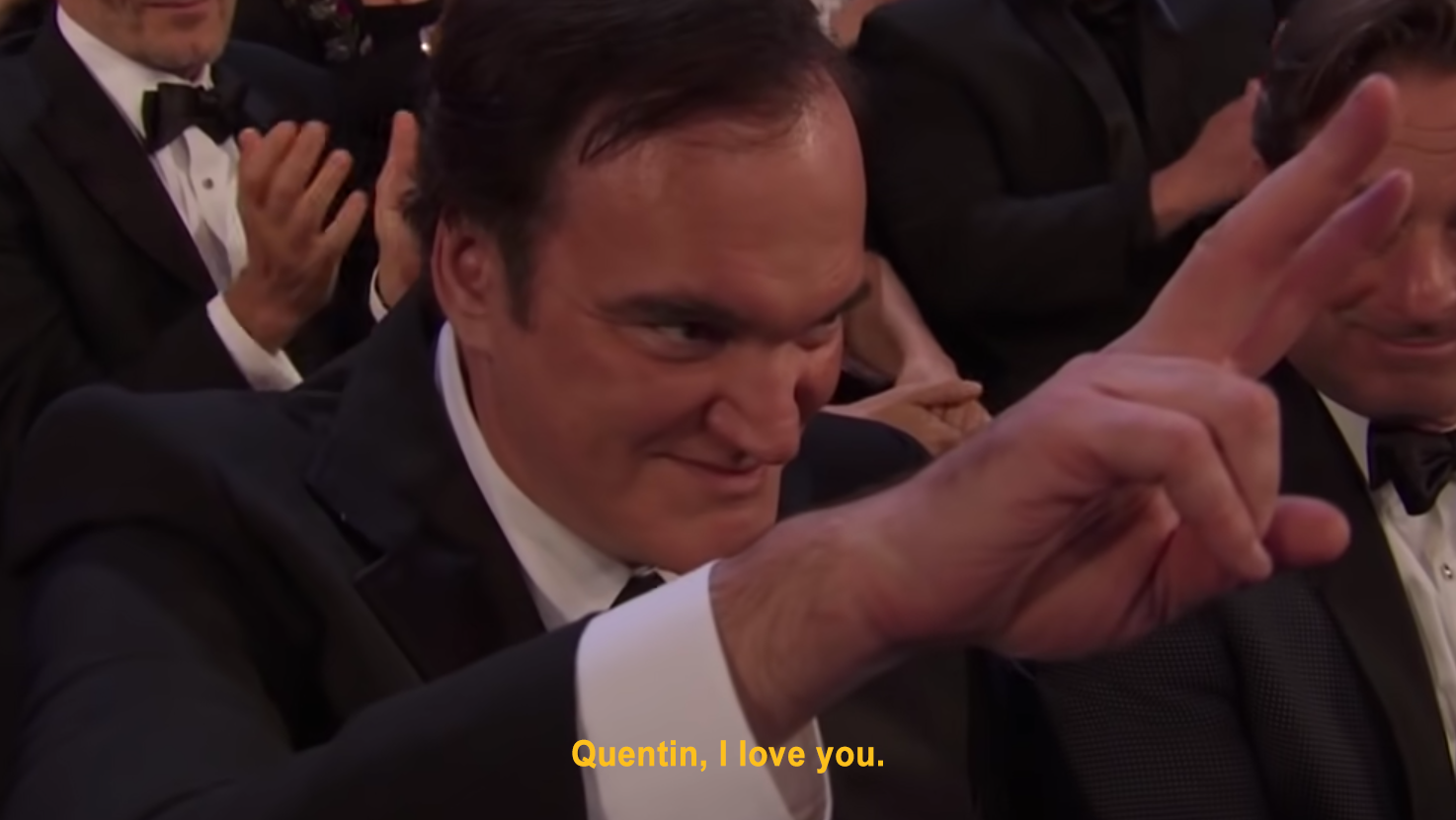

When Bong Joon-ho won the Best Director Oscar for Parasite, he again presented a memorable speech. “When I was young and studying cinema, there was a saying that I carved deep into my heart, which is: ‘The most personal is the most creative.’ That quote was from our great Martin Scorsese. When I was in school, I studied Martin Scorsese’s films. Just to be nominated was a huge honor. I never thought I would win. When people in the U.S. were not familiar with my film, Quentin always put my films on his lists. He’s here. Thank you so much. Quentin, I love you.” In addition to the admiration, love, and appreciation Bong shows his fellow filmmakers before a public audience, he offers various inspiring insights for artists and filmmakers in this speech.

“The most personal is the most creative.” While all art endeavors to reach an audience, the key to connecting with an audience is for the artist to be true to the work and to oneself. When we see a Color Field painting, we know it is by Mark Rothko without having to see the signature on the canvas. We know these imagery-filled verses are by Pablo Neruda when we read the lines “Quiero hacer contigo/ lo que la primavera hace con los cerezos. (I want to do with you/ what spring does with the cherry trees.)” There are details that mark the nature and presence of the artist in his or her work. The most personal is the most creative and, as a result, the most unique. For all artists: be true to your style, be true to you.

Bong also hints at one of the most valuable ways of enriching your artistic style when he honors Martin Scorsese in this speech. In mentioning his studies of Martin Scorsese’s films, Bong brings to mind Scorsese’s memorable advice to young filmmakers: “I’m often asked by younger filmmakers, ‘Why do I need to look at old movies?’ I’ve made a number of pictures in the past twenty years. And the response I find that I have to give them is that I still consider myself a student. The more pictures I’ve made in the past twenty years the more I realize I really don’t know. And I’m always looking for something to, something or someone that I could learn from. I tell them, I tell the younger filmmakers and the young students that I do it like painters used to do, or painters do: study the old masters, enrich your palette, expand your canvas. There’s always so much more to learn.” In studying the old masters, you nourish your evolution as an artist and further your understanding of who you are as an artist. You also discover that the details, ideas, and habits that resonate from others and their works are often reflections of your own artistic voice.

“If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants,” said Isaac Newton. “The dwarf sees farther than the giant, when he has the giant’s shoulder to mount on,” wrote Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Study the old masters in order to enrich your palette and in order to go further than you could all by yourself. As Jim Jarmusch shares in his Golden Rules to Filmmaking: “Nothing is original. Steal from anywhere that resonates with inspiration or fuels your imagination. Devour old films, new films, music, books, paintings, photographs, poems, dreams, random conversations, architecture, bridges, street signs, trees, clouds, bodies of water, light and shadows. Select only things to steal from that speak directly to your soul. If you do this, your work (and theft) will be authentic. Authenticity is invaluable; originality is nonexistent. And don’t bother concealing your thievery—celebrate it if you feel like it. In any case, always remember what Jean-Luc Godard said: ‘It’s not where you take things from—it’s where you take them to.’”

After Bong Joon-ho salutes Martin Scorsese, he mentions the support he has received from fellow filmmaker Quentin Tarantino and shows appreciation and gratitude for his endorsement. Here Bong highlights the importance of community, of building your tribe and supporting your fellow artists. Together, we grow stronger. Together, we blossom because we nourish one another. A tribe of artists cultivates creative energy for the use of all. In a world where everyone is fighting to make their mark, the true fight is won by helping each other to make their mark. Thus, it is invaluable to find your tribe, the people who nourish you in your career and work.

Bong Joon-ho has presented the world a 21st Century masterpiece of cinema with Parasite, which enters a filmography of unique, thrilling, and deeply layered films. He proves that a film can be both entertainment and art, or rather that a film that is made out of meaningful and genuine artistic expression can engage audiences around the world. It was magnificent to witness Parasite win award after award, especially in a system that often disengages with the perspective of those who love the art of cinema. Truly, the film world needs Bong Joon-ho.