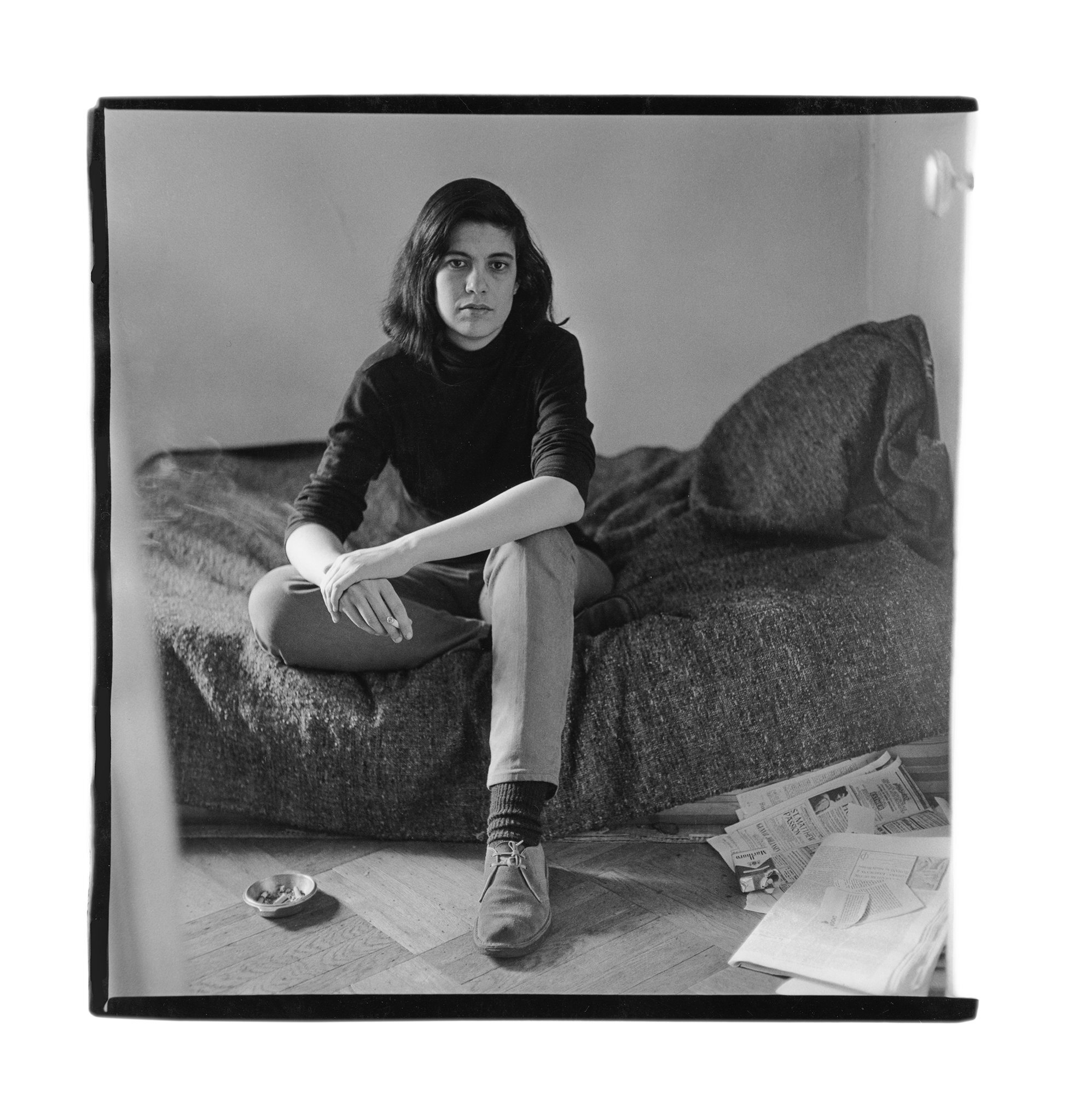

“Susan Sontag alone on a bed. N.Y.C. 1965” by Diane Arbus.

(Note: Some links may be affiliate links. We may get paid if you buy something or take an action after clicking one of these.)

A brilliant thinker, Susan Sontag is a writer of many great things. Her books shed light on culture and society, on cinema and literature, on so much and with equal intensity and reverence. They echo the voice of a writer who approached subjects with both the mind and heart and with an urgency to relate all of our concerns. Is that actually possible? Well, she made it feel so. She teaches you to think and reflect, to evolve, to see. Of the many topics her books address, art is an essential one. Her essay “An Argument Against Beauty” in the book At the Same Time: Essays and Speeches, teaches us how to think and reflect on the evolution of the definition of artistic beauty and to see it with an openness to its importance in life. Here are 5 insights on beauty in art from Susan Sontag.

1) Beauty, it seems, is immutable, at least when incarnated—fixed—in the form of art, because it is in art that beauty as an idea, an eternal idea, is best embodied. Beauty (should you choose to use the word that way) is deep, not superficial; hidden, sometimes, rather than obvious; consoling, not troubling; indestructible, as in art, rather than ephemeral, as in nature. Beauty, the stipulatively uplifting kind, perdures.

2) Beauty defines itself as the antithesis of the ugly. Obviously, you can’t say something is beautiful if you’re not willing to say something is ugly. But there are more and more taboos about calling something, anything, ugly. (For an explanation, look first not at the rise of so-called "political correctness," but at the evolving ideology of consumerism, then at the complicity between these two.) The point is to find what is beautiful in what has not hitherto been regarded as beautiful (or: the beautiful in the ugly).

3) Today, good taste seems even more retrograde an idea than beauty. Austere, difficult "modernist" art and literature have come to seem old-fashioned, a conspiracy of snobs. Innovation is relaxation now; today's E-Z Art gives the green light to all. In the cultural climate favoring the more user-friendly art of recent years, the beautiful seems, if not obvious, then pretentious. Beauty continues to take a battering in what are called, absurdly, our culture wars.

4) One calls something interesting precisely so as not to have to commit to a judgment of beauty (or of goodness). The interesting is now mainly a consumerist concept, bent on enlarging its domain: the more things become interesting, the more the marketplace grows. The boring—understood as an absence, an emptiness—implies its antidote: the promiscuous, empty affirmations of the interesting. It is a peculiarly inconclusive way of experiencing reality.

5) The responses to beauty in art and to beauty in nature are interdependent. As Wilde pointed out, art does more than school us on how and what to appreciate in nature...What is beautiful reminds us of nature as such—of what lies beyond the human and the made—and thereby stimulates and deepens our sense of the sheer spread and fullness of reality, inanimate as well as pulsing, that surrounds us all.

A happy by-product of this insight, if insight it is: beauty regains its solidity, its inevitability, as a judgment needed to make sense of a large portion of one's energies, affinities, and admirations; and the usurping notions appear ludicrous.

Imagine saying, “That sunset is interesting.”

(Note: As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.)